…And every relationship in its rightful name. Indians regard even cousins and aunts/uncles thrice removed as part of the ‘family’ and, insist on according them the needed importance and respect. Why is Indian society driven by such an elaborate system of kinship?

The value Indians place on their relationships with members of their extended family is so deep that they have very specific terms for these relatives. In English we simply say ‘aunt’ to denote our father’s sister or our mother’s sister, whereas Indians differentiate between them and use specific names to indicate the precise relationship. This happens across India’s many languages. For instance, in the Tamil language your father’s sister is athai and your mother’s sister is chitti. In Marathi, spoken in Maharashtra, the word for your paternal aunt is atya and your maternal aunt is maushi.

Taking a Closer Look

God forbid you call your mother’s younger sister badi ma or your mother’s older sister masi, the Hindi words which depict the opposite meaning of these relationships. To clarify, badi ma refers to one’s mother’s older sister, and masi to one’s mother younger sister. Each aunt has a special descriptor showing respect for that relationship, and both would feel hurt if referred to by the ‘wrong’ term. The importance given to a particular relationship that you share with a family member, and the particular way you call and address relatives, is an important part of Indian culture, which is driven by an elaborate system of kinship based on language, community and family.

The concept of family extends far beyond the immediate family circle, and connections with one’s extended family are sought out and valued. If people from, say, Mumbai, Delhi and Chennai are socialising together, those from Mumbai will inevitably be drawn towards their fellow Mumbaiites and – within a very short time – start finding similarities and connections: Where this person’s aunt went to college with that person’s uncle, and where this person’s sister was living next door to that person’s second cousin. There is always some relative who will be a binding factor and the group will knit more closely, start finding commonalities and form real friendships just in one evening because relationships mean so much to Indians.

Of Legend and Myth

Kinship is at the heart of the Mahabharata, ancient India’s epic tale. At the core of the story is a struggle for inheritance between two sets of paternal cousins, the Kauravas and the Pandavas, who become bitter rivals and oppose each other in war for possession of their ancestral kingdom. Modern TV soap operas have taken their inspiration from the epics. They are still set within big joint families where several generations live together and the relationship between a mother-in-law and daughter-in-law is often at the heart of the story. Just like the Mahabharata, these are family sagas where the forces of good and evil collide.

The Here and Now

The significance Indians place on relationships can be witnessed in the world of work as well as the family. A recommendation from an individual who has proved a trusted and valuable employee that the company hires a member of the family will be taken seriously by colleagues. For an HR department, that can be a reference good enough to take up when considering hiring someone. Unlike in the West, where such an arrangement is seen as nepotism, it is not seen as unethical in India to favour the relative of a respected employee.

Cultural Expressions

If you go to an Indian wedding, you will be amazed at how many people are invited. The truth is if any relative is not invited, there will be hell to pay! You can’t even choose to leave out a second cousin or a cousin three times removed. If you invite one cousin who is a second cousin, you have to invite all the cousins who are second cousins. At some point, the parents of the bride or groom will have to decide where to draw the line – perhaps they’ll invite everyone up to relatives three times removed!

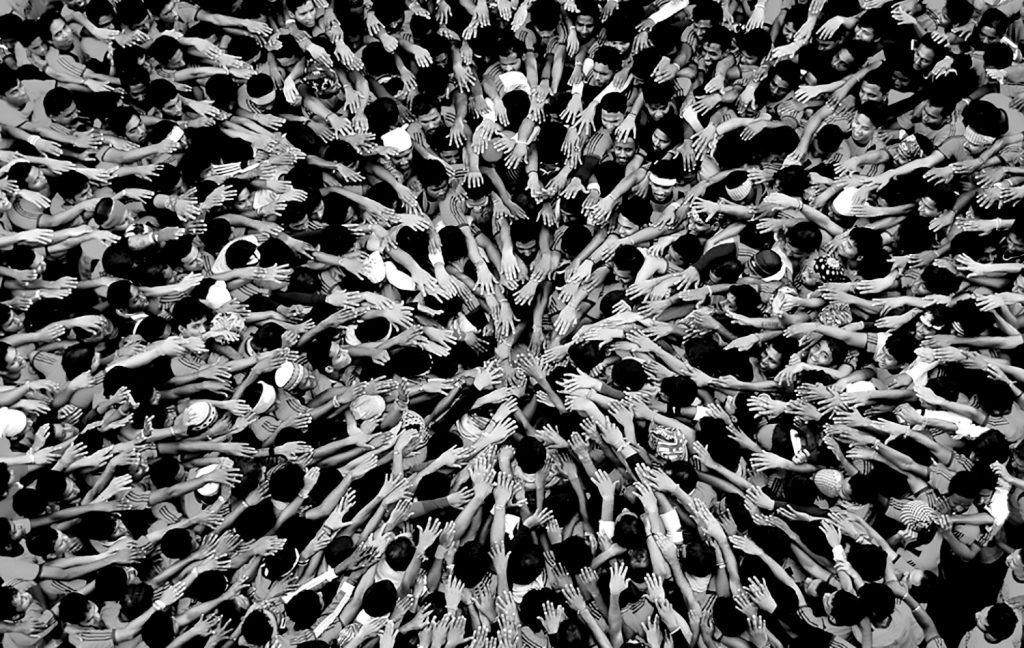

The point here is that relationships matter in all rites of passage and milestones of life. Involving everyone when there is good news to celebrate is automatic in Indian relationships, but so it is when there is sadness to mark, too. When someone dies, you still relate to the deceased person as a fellow human being and you just show up at the doorstep of their home, whether friend or neighbour, and even if you didn’t know them very well. There is no concept of quiet or isolated mourning. This can be good and bad. Many, many people will come to pay their respects when someone has died, thronging the house; to a non-Indian, this will appear overwhelming. However, it also alleviates the sorrow, because sorrow shared is sorrow halved. It is the very opposite of the Western world, where people mourn in private.

World Echoes

It is said that the things a culture truly values come across in its language. The Inuit people, for example, have numerous words for ice, signifying, for example, if it’s thin ice, thick ice, sheet ice or flakes of ice, whilst in the African savannah there are several different words for grass that denote if the grass is dry, or green or long-stemmed. Ice is an important part of the culture of the Inuit, and in Africa grass is to be valued. The way that relationships have unique names in India shows how this is a driving force of Indian culture.

In Conclusion…

Older family friends and even strangers are often called ‘aunty’ or ‘uncle’ in India as a sign of respect. This may seem strange to non-Indians, but it is evidence of how relationships are formed quite easily in India. More interestingly, such relationships can be as (and sometimes, even more) lasting as those formed by blood and kinship. Many expats profess their surprise at how their children are encouraged to call their friends or colleagues ‘uncle’ or ‘aunty’, but also share heart-warming stories of birthday gifts or warm greetings sent years after they have returned home.