Susan Philip goes on an artistic journey to cherry pick crafts from the North, East, Centre, West and South of India that make our country unique and exceptional. Some of these are well-known, others not so much, and in danger of dying out. Together we take a look at some of those

A land of colour. A land of beauty. That’s India. Here, beauty is present on a scale as magnificent as the Taj Mahal and also in a simple forearm’s length of strung jasmine flowers. In India, beauty is fashioned by lamplight and over woodfires, on looms and on mud walls. It is created as much by unlettered people with no knowledge of technology or the outside world, as by those who have had the education and exposure to hone their talents to new levels. And the world loves all these bits of beautiful India.

Handicrafts, made for the most part in ways that have been handed down from one generation to the next, make up a significant part of the country’s exports. They range from rich carpets to warm socks, from simplistic Worli paintings to intricately detailed Rajasthani miniatures, from delicate Lucknow Chikan embroidery to opulent Zardosi work, from jewel-toned blue pottery to humble diyas, from charming Chennapatna toys to ornate Aranmula mirrors. The list can go on. And on.

Feather-light Fashion

Have you experienced the soft warmth of a pure Pashmina shawl? It’s a sensation you’re unlikely to forget. Once found only in the wardrobes of royalty because of the price, these stoles or shawls became much sought-after in 18th and 19th century Europe, especially France. It was originally known as ‘Cashmere’ in the West because of its association with Kashmir. Beloved of Queen Marie Antionette and Josephine, wife of Napoleon Bonaparte, it is still a status symbol for the luxury-loving.

But the origins of the Pashmina are far from luxurious. From lonely, nomadic shepherds tending their flocks in the barren, snowy heights of the Himalayas to women bent over spinning wheels in tiny cottages, from centuries-old wooden printing blocks to vegetable dyes and skeins of coloured threads, the Pashmina passes through many hands and processes.

The art finds mention in books dating as far back as the 3rd century BC. The name comes from the Persian Pashm, meaning ‘made from wool’; in this case, the softest wool, spun chiefly from the undercoat of the Capra Hircus, or the Himalayan Goat, also known as Chyangra. The classic base colour of the Pashmina is cream. The entire process of making an authentic Pashmina is laboriously done by hand as the Chyangra’s hair is too fine to withstand mechanisation. A single piece can take up to 250 man-hours to complete, and prices vary depending on the quality of the wool and craftsmanship.

Celebrating Grain

Celebrating Grain

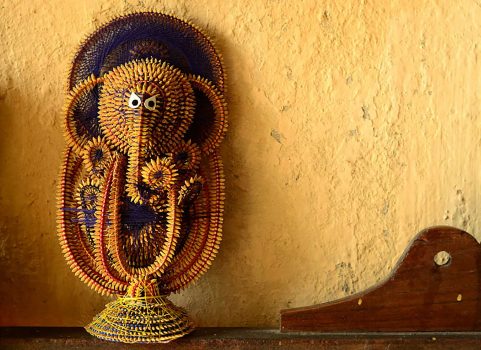

In the Chota Nagpur plateau, which forms part of Jharkhand, and neighbouring states like Odisha and Assam, women and children settle down after their chores with a pile of unhusked paddy, thin slivers of bamboo sticks and balls of coloured thread. They belong to the Munda tribe. They are engaged in Oryza Sativa (Asian rice) craft, practised now by only very few families.

The bamboo sticks are yellow-hued, having been previously soaked in auspicious turmeric water and sun-dried. Nimble fingers knot equisized grains of paddy one by one on to parallel pairs of bamboo sticks, to make a thin garland. These garlands form the base for the handicrafts.

The Mundas were nomadic hunter-gatherers before they settled down to agricultural activity. Once the paddy garlands have been made, the men take over. They coil and twist the garlands into images of Lakshmi, Goddess of Wealth, Ganesh, the elephant-headed Remover of Obstacles, peacocks, pots and the like. After embellishing them appropriately, they go from village to village hawking the artefacts.

A few other tribes, like the Devaguru, also practise this traditional art. But it’s a dying skill. The prices commanded by the intricately wrought pieces are not commensurate with the labour and expertise involved, and it certainly doesn’t constitute a livelihood. Yet, the Munda, the Devaguru and other tribes of the region believe it is their vocation to create these Dhana Murthies. Little known even in other parts of India, these artefacts have a unique ethnic beauty.

Rustic Charm

It’s one of the oldest metal crafts known to man. In fact, the earliest examples can be traced back to the Indus Valley Civilisation – the dancing girl of Mohenjo-Daro is iconic. Central Indian tribes have passed this skill down the centuries, and today, this non-ferrous metal casting craft is known by the name of the tribe, which is most associated with it – the Dokras.

Dokra craft items are much in demand in India and abroad for their rustic, elemental beauty. The process, though, is quite complicated. The first step is to make a core shape of clay and cow dung. Thin ropes of bees’ wax blended with resin are coiled around the core shape. Details and embellishments are worked in. A clay coating is given on the outside, taking the shape of the coiled ropes in negative. The mould is baked after making vents for the wax to drain out as it heats. The gap left by the wax is filled with molten metal, and when this sets, the outer shell is chipped away to reveal a unique artefact. No Dokra piece is the same as another, because the process necessitates individual moulds for each item.

The technique is traditionally used to make figurines of deities, lamps, bells and other objects used in worship, as well as replicas of animals and items used in daily life. Today, items like photo frames are also made, to cater to contemporary tastes.

Crafted to Last

Crafted to Last

Cradles, burnished and decorated with painted designs, are treasured heirlooms in many Gujarati families. They last generation after generation, looking just as beautiful as when they were made over a hundred years ago. That’s because they are Sankheda pieces. Crafted from teak, embellished with floral or geometric patterns and polished to emit a glow that years can’t dim.

Considered auspicious, Sankheda pieces are often gifted to newly married couples. They are also frequently gifted to visiting foreign dignitaries.

This unique craft, which has a GI tag, is named after its hub – the village of Sankheda near Vadodara. The village itself takes its name from the word Sanghedu, meaning lathe in Gujarati. The wood for each individual part of a piece of furniture is turned by hand on lathes. Tin foil is pounded with a type of glue into a homogenous mass, and used to hand-paint intricate patterns on the wood. The disparate pieces are then assembled into a beautiful whole. Vegetable dyes, agate and clear lac are some materials used to give Sankheda furniture its distinctive, gleaming, burnt-orange colour.

Around 100 families in Sankheda village are involved in producing the furniture. Today, mechanisation has been introduced, and technology has made it possible to make Sankheda furniture in black, blue, green and even ivory. Melamine is used in place of lac. But purists will not be satisfied with anything but the traditional way of production.

Lock Land

You might think that locks are mundane, prosaic things, far removed from the realms of art and aesthetics. Yet, they’re an art form in themselves – at least in and around Tamil Nadu’s Dindigul, known as ‘Lock City’. The locks made here have acquired an identity of their own, and are specifically sought after. This unique identity has been acknowledged through the recent grant of the GI tag to the ‘Dindigul lock’.

The fact is, there is no one Dindigul lock. There are a variety of them, each with its own specific characteristics. Some have single keys, others have many. The keys of some are so unique that if they’re lost, a replacement can be made only in Dindigul.

They’re known by names as poetic as mango lock, trick lock, bell lock and book shutter lock. There’s even a killer lock, which is so designed that if the wrong key is inserted, a knife pops out, chopping off or at least hurting the fingers of the unauthorised or negligent user.

Perhaps it was the abundant availability of iron that made locks a trademark industry of this region. Although most pieces are made of iron, gold locks can be made to order.

Despite modern technology, Dindigul locks are still preferred by government institutions, temples and even prisons. Such is their reputation for safety! They are also known for their durability, as the average piece is said to last well over 50 years

The Dindigul lock industry is more than 500 years old. Time was when there were many big lock-making factories in the region, employing over a 100 people each. Now, there are only a few small units in and around the town. The grant of the GI status will hopefully revive interest in this unusual craft.

These are just a sample of the myriad arts and crafts of India, behind each of which lies fascinating history – inside stories to be told another time!