Iranian Artist Saleh Kazemi came to India in search of the spiritual haven depicted in a novel. He found rich and iconic beauty when he travelled through Goa – which he has captured in his drawings. Something else comes to the fore as well – a deep resonance with the ancient tenets of India’s spiritual tradition, which he has never heard of before

It happened in Rome. On a balmy July afternoon. A lithe Iranian artist was at a luncheon, ignoring the wine and running through the list of countries he wants to visit. The countries neatly categorised into ‘easy’ and ‘difficult’ columns. India fell in Saleh Kazemi’s ‘difficult’ category. Long-haul travel. Expensive. That afternoon, an India-montage invaded Kazemi’s mind space. Vignettes gathered from the pages of Hermann Hesse, the German Nobel laureate whose father and grandfather lived in India as evangelists. The India-connection was not a consequence of catechism. It was Siddhartha, Hesse’s book that deals with the spiritual journey of self-discovery of a man named Siddhartha who lived during the Gautama Buddha. Of an unseen country, Kazemi knew of India only through Siddhartha.

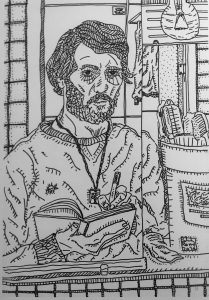

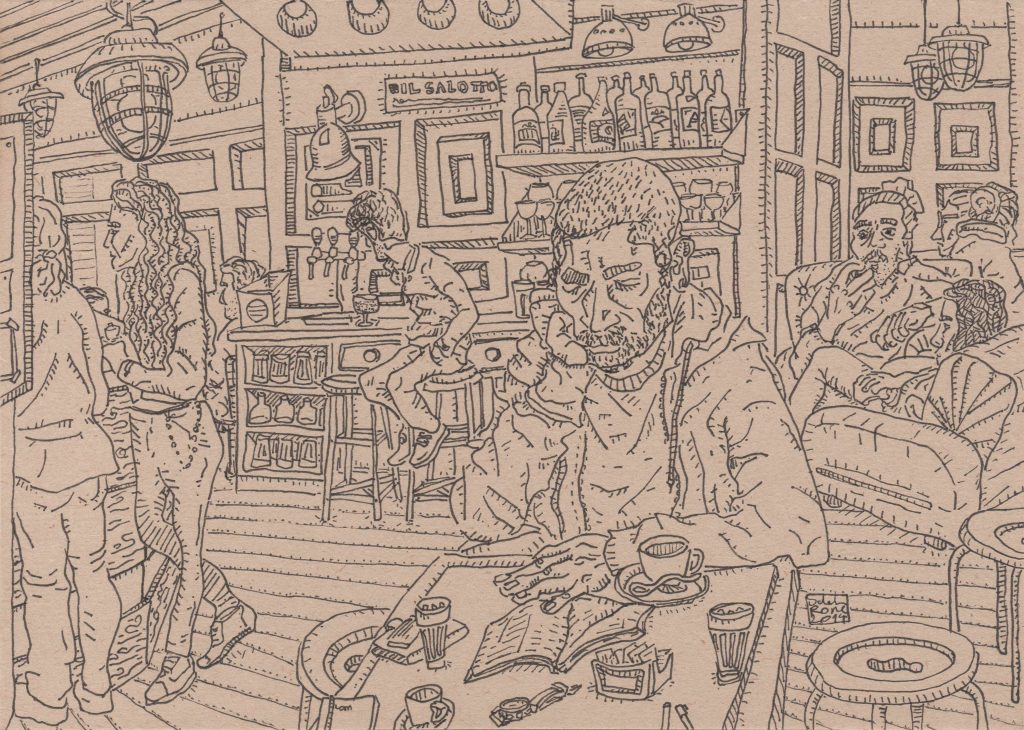

Suddenly, fate intervened. Jenepher Bramble, the host who calls London, Rome and Goa her home, uttered a one-liner: “Why don’t you come to India?” As if on cue, India jumped from Kazemi’s ‘difficult’ to the ‘easy’ list. Six months later, Kazemi flew into India, his eyes laden with the idea of a spiritual India borrowed from Hesse’s musings. It was his art that brought Iranian Saleh Kazemi to Goa where, for three months, he walked past mud houses, drove through narrow lanes, spent hours in marketplaces picking images for his sketchbook. That is what Kazemi does. Draws. Two months and nearly 70 drawings later, he exhibited his drawings in the Museum of Goa. Titled Mirror of Everyday Life, the two-week-long solo looks at Goa through the eyes of an Iranian artist who reads poetry, plays the harmonica, names Egon Schiele, the Austrian artist, as his favourite master, and confesses he has no imagination (he is purely ‘logical’).

Saleh Kazemi (his given name translates into ‘peace’) knows not where his art comes from. Certainly, there are no traces of art in his DNA helix. Born in Tehran, he moved to Rome after high school because “it was the easiest, cheapest way to enter Europe”. He studied graphic design, took up photography assignments in Germany, Italy and Switzerland, but never thought of drawing as his final calling. On a fortuitous train journey, he read the last page of the last Persian book he had. When ennui crept, he pulled the sketchbook and a 0.05 black ink pen from his backpack and drew. His fellow-passengers, the window, the coffee mug on the table… Those deft strokes in black have a pattern. The eyebrows are striped, the hair wavy and the knuckles gnarled. A pattern repeated in his Goan drawings, too. Strangely, there are only Goan women in those square white handmade paper. Intrigued, I ask Kazemi why. “In my mind, I had an idea about Indians. Very iconic, very nuanced, very distinct characteristics. But I found none of them in the Goan men. In women, yes. The Goan women I saw at the marketplace had such iconic Indianness. That is why I ignored the men and drew only women.” And is there an unforgettable image? I ask again. “Yes, the colours. The pinks and the reds that the women wear. Such vibrant colours. Such warmth.” There is not a speck of colour in his sketchbooks, but the pinks and reds did get etched in Kazemi’s mind.

During his three-month stay in India, Kazemi camped in Goa and ambled around Mumbai briefly. When he landed in India, his eyes were laden with images strung by Hesse in Siddhartha. Was that the India that he actually saw? I rake the artist’s mind. “No. I had thought of India as a spiritual place. I assumed I will find spirituality in the air, but, no, I did not. Instead, I found a Hawaii-Goa, cluttered with rich foreigners and reckless drivers.” There was a hint of disappointment in Kazemi’s soft voice and I harked back to Hesse’s confession that the idealised image of India as shaped by the stories told by his grandfather Hermann Gundert proved elusive. Hesse was appalled by the heat, the dirt, the colonialism, the social conditions in India.

During his three-month stay in India, Kazemi camped in Goa and ambled around Mumbai briefly. When he landed in India, his eyes were laden with images strung by Hesse in Siddhartha. Was that the India that he actually saw? I rake the artist’s mind. “No. I had thought of India as a spiritual place. I assumed I will find spirituality in the air, but, no, I did not. Instead, I found a Hawaii-Goa, cluttered with rich foreigners and reckless drivers.” There was a hint of disappointment in Kazemi’s soft voice and I harked back to Hesse’s confession that the idealised image of India as shaped by the stories told by his grandfather Hermann Gundert proved elusive. Hesse was appalled by the heat, the dirt, the colonialism, the social conditions in India.

Kazemi, however, is not done with India yet. He wants to return, to hold another exhibition, to hire a car and drive through ‘village after village’ to see the real India. Not the Hawaii-Goa India but the real India. To find spirituality. To meet people. To understand a culture. And, of course, to travel; the last being Kazemi’s refrain. “All my personal belongings can fit in a bag. I have no concept of a permanent home. I like the lightness of Being. I wanted to play the piano, but it is too heavy. I play the harmonica because I can carry it along. I gave away my heavy DSLR cameras and bought the lightest/slimmest Fuji camera. I only want to travel, see the world. And learn. And understand.”

Kazemi, however, is not done with India yet. He wants to return, to hold another exhibition, to hire a car and drive through ‘village after village’ to see the real India. Not the Hawaii-Goa India but the real India. To find spirituality. To meet people. To understand a culture. And, of course, to travel; the last being Kazemi’s refrain. “All my personal belongings can fit in a bag. I have no concept of a permanent home. I like the lightness of Being. I wanted to play the piano, but it is too heavy. I play the harmonica because I can carry it along. I gave away my heavy DSLR cameras and bought the lightest/slimmest Fuji camera. I only want to travel, see the world. And learn. And understand.”

Sitting cross-legged on the floor, I was listening to Kazemi and his concept of existence, ideas that are oft-repeated in the Vedic scriptures. Did he borrow from Persian philosophy? “I have not delved into Persian philosophy. My earliest recollection of detachment and spirituality is from W. Somerset Maugham’s final novel, The Razor’s Edge (1944). I was barely 12 when I read the story of Larry Darrell, an American pilot traumatised by his experiences in World War I, who sets off in search of some transcendent meaning in his life.” Kazemi did not mention it, but I know that the title of Maugham’s novel comes from a translation of a verse in the Katha Upanishad (Part 1, Chapter 3, Verse 14):

उत्तिष्ठत जाग्रत प्राप्य वरान्निबोधत ।

क्शुरस्य धारा निशिता दुरत्यया दुर्गं पथस्तत्कवयो वदन्ति ॥ १४ ॥

Uttisthata jāgrata prāpya varānnibodhata |

kśurasya dhārā niśitā duratyayā durgam

pathastat kavayo vadanti ||

“Arise, awake; having reached the great, learn; the edge of a razor is sharp and impassable; that path, the intelligent say, is hard to go by.”

Saleh Kazemi has not read the Katha Upanishad, he knows not a word of Sanskrit; but somewhere in bold black strokes in the Mirror of Life drawings and his own life and art, the artist practises minimalism and seeks salvation. Not for him the ordinary, the mundane, the dreary. Saleh Kazemi exists in another world.