Born on October 2, 1869, in Porbandar, Gujarat, Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi grew up with values that would not only lovingly give him the title of babuji one day but also make him a role model for world leaders across generations. Susan Philip takes a look back at the moments that defined the Father of the Nation

Born on October 2, 1869, in Porbandar, Gujarat, Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi grew up with values that would not only lovingly give him the title of babuji one day but also make him a role model for world leaders across generations. Susan Philip takes a look back at the moments that defined the Father of the Nation

Born on October 2, 1869, in Porbandar, Gujarat, Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi grew up with values that would not only lovingly give him the title of babuji one day but also make him a role model for world leaders across generations. Susan Philip takes a look back at the moments that defined the Father of the Nation

As a boy, there wasn’t much to set Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi apart from others of his age. His life ran the normal course. As was the custom then, he got married when he was around 13, to a local girl, Kasturba. But from there, his life started veering off the traditional path. Although he was something of a rebel, he also took to introspection, and thought far more deeply than was the norm for his age. He went on to study law in England, and moved to South Africa as a barrister. There his life took a decided turn away from the beaten track. He returned to India, and went from being an aatma – a soul – to a mahatma, a great soul.

‘Impressions of Gandhi? You might well ask for someone’s impression of the Himalayas’ – George Bernard Shaw

Without any of the modern public relations aides, no social media, no publicity drives, this great man succeeded in arousing a motley collection of people from diverse economic, social and religious backgrounds to willingly embrace suffering, humiliation, deprivation and detention for the sake of the ideal of a country where the mind is without fear, and the head can be held high.

Power from within

Power from within

Putlibai, Mahatma Gandhi’s mother, practised the ideals of Hinduism, vegetarianism and also religious tolerance. She influenced her young son deeply. He must have imbibed his tendency to ponder on deeper truths from her. The way one’s selfish desires can affect others is not a topic most teenagers dwell on. But Mohandas did, after he gave in to a physical whim and so missed his father’s dying moments. That was probably the definitive moment that set him thinking of the need for self-control and self-denial for the greater good.

Divine truths

When he was 19, Mohandas was offered a chance to study in London. His orthodox community was aghast. They warned him that he would be irrevocably polluted if he crossed the seas. But the young man decided to follow his own star. He studied law at the Inner Temple, London. For a while he shrugged off the principles of his religion and upbringing, and ‘lived it up’. But then he came in contact with the stalwarts of the Theosophical Society and Madam Blavatsky and Annie Besant helped him reconnect with his roots. He was influenced by many thinkers and idealists. He began pondering about the underlying similarity of the precepts of all religions. ‘My young mind tried to unify the teachings of the Bhagavad Gita, the Light of Asia and the Sermon on the Mount,’ he explained. The basic equality of all humanity was another concept that engaged his mind. And so, another major step was taken on the spiritual journey.

Not cooperating to win

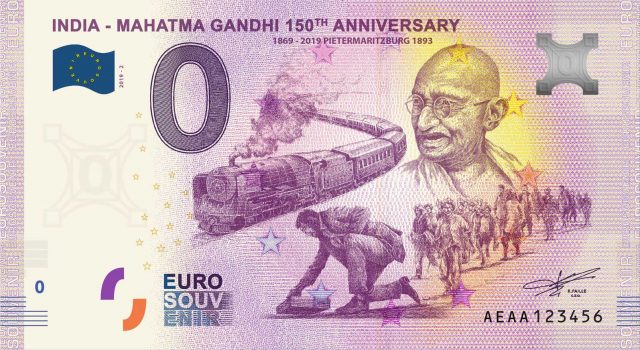

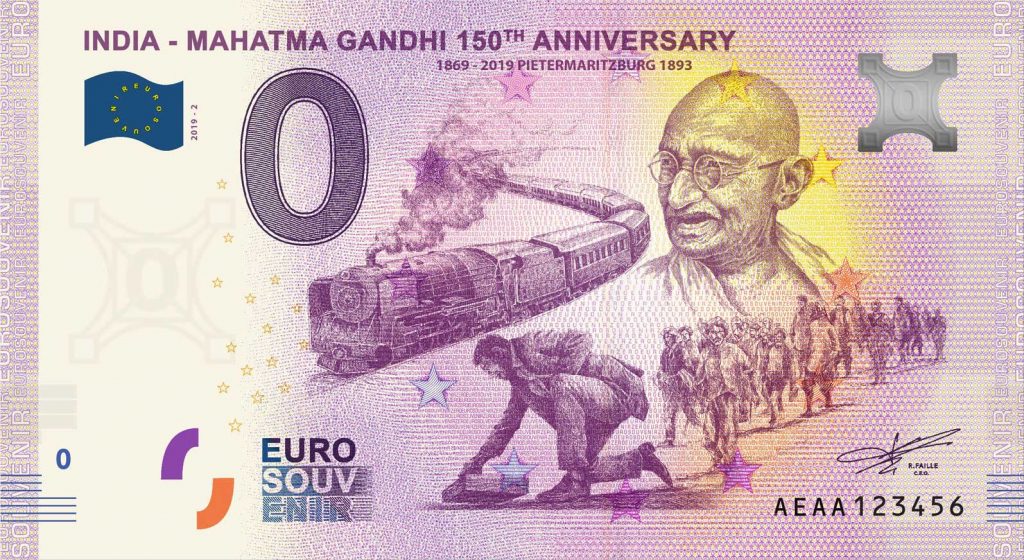

Thought was converted into action on a windswept platform in Durban, South Africa, after the momentous incident where he was thrown off a train on the basis of nothing other than the colour of his skin. The young barrister set up the Natal Indian Congress to fight against racial discrimination.

From that milestone on, Mohandas Gandhi started refining on his ideas of civil disobedience and non-cooperation. He was to say later, with customary modesty, that there was nothing about these ideas that could be called ‘Gandhian’ as both concepts were ‘as old as the hills’.

The force of truth

Back in India, long rides across the country in third-class railway carriages and the uprising by indigo farmers at Champaran protesting against exploitation by the British were catalysts to the next big steps in the journey from Mohandas to the Mahatma. The concepts of non-cooperation and civil disobedience might have been ‘nothing new’, but it was Gandhiji who developed the systematic approach of Satyagraha (truth force), a moral weapon using these two concepts infused with the principle of non-violence (Ahimsa), to fight injustice meted out by temporal enemies. The terms moral and temporal are contradictory, no doubt, but the ‘Mahatma’ in Gandhi succeeded in negating that contradiction and making the weapon astonishingly effective.

I believe that Gandhi’s views were the most enlightened of all the political men in our time. We should strive to do things in his spirit: not to use violence in fighting for our cause, but by non-participation in anything you believe is evil.”

– Albert Einstein

The Jallianwala Bagh massacre escalated Gandhiji’s endeavours into a quest for out-and-out independence for India. He travelled to the United Kingdom as part of this quest, and met both adulation and disdain. The Kheda agitation, the Non-cooperation, Civil Disobedience and Quit India movements were all spearheaded by him. He went on fasts as a means to gaining political concessions from the British rulers of India. In consequence, the bars of prison cells became as familiar to him as the rustic beauty of his Satyagraha Ashram on the banks of the Sabarmati.

Towards inclusivity

But side by side with the political agenda, the Mahatma was pursuing another agenda – that of promoting equality among man and man, and man and woman. Appalled at the discrimination prevalent in the subcontinent on the basis of caste, creed and gender, he set out on a mission of inclusivity. He coined a name for the marginalised and often ostracised castes – Harijan, or people of God. He made himself comfortable in the colonies of these Harijans, giving them a taste of the brave new world he was seeking to create. Women’s empowerment was a cause dear to his heart, and, by involving them in his campaigns and agitations, he gave them a foothold in public life. He also opposed socially oppressive practices like child marriage and ill-treatment of widows.

Just an old man in a loincloth in distant India. Yet, when he died, humanity wept’ – Louis Fisher (American journalist)

Gandhiji’s idea of non-violent non-cooperation ultimately yielded results, but they weren’t quite what he wanted. He had never envisaged an India without Muslims. He was devastated at the Partition, and while the rest of the subcontinent celebrated freedom from the British yoke, Gandhiji spent August 15, 1947, in prayer and fasting. A few months later, when bullets slammed into his body, his last words were Hey Ram! A light went out. The atma left the body.

But the Mahatma lives on.

His firm renunciation of violence as a means to achieve justice should not have worked by the world’s standards, but work they did! Civil rights leaders from Martin Luther King Jr. to Nelson Mandela, from Cesar Chevaz to Ibrahim Rugova, adopted his revolutionary ideas, and, in consequence, the lives of thousands upon thousands of people all over the world changed for the better.

“Throughout my life, I have always looked to Mahatma Gandhi as an inspiration, because he embodies the kind of transformational change that can be made when ordinary people come together to do extraordinary things. That is why his portrait hangs in my Senate office: to remind me that real results will come not just from Washington – they will come from the people.” – Barack Obama

Impacting the Mahatma

In formulating his revolutionary ideas, Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi was influenced by a range of people and books. The Bhagavad Gita was a perennial source of inspiration. So was The Bible. Leo Tolstoy’s The Kingdom of God is Within You, Henry Thoreau’s essay on Civil Disobedience, and John Ruskin’s Unto This Last left deep impressions on him. He found much to admire in Prophet Mohammed and The Buddha.

At different stages in his life, Gandhiji influenced, and was influenced by various people. He acknowledged Shrimad Rajchandra (Raychand), a Jain philosopher, as a spiritual Guru, while Gopalakrishna Gokhale was his political mentor.

Hermann Kallenbach was a Lithuanian Jewish architect who Gandhiji described as his ‘soulmate’. Kallenbach was with Gandhiji during the entire course of the civil disobedience movement in South Africa. It was he who donated the land now famous as the Tolstoy Farm which Gandhiji ran for the Satyagrahis. Today, Rusné, a small island in Western Lithuania, is home to the Gandhi-Kallenbach monument commemorating this friendship as also the cordial relationship between India and Lithuania.

Hermann Kallenbach was a Lithuanian Jewish architect who Gandhiji described as his ‘soulmate’. Kallenbach was with Gandhiji during the entire course of the civil disobedience movement in South Africa. It was he who donated the land now famous as the Tolstoy Farm which Gandhiji ran for the Satyagrahis. Today, Rusné, a small island in Western Lithuania, is home to the Gandhi-Kallenbach monument commemorating this friendship as also the cordial relationship between India and Lithuania.

C.F. Andrews was a priest, Christian missionary, educator and social reformer who worked in India for a while. He went to South Africa, heeding a request by Gopalakrishna Gokhale, and there he met Gandhiji. It was Andrews who persuaded Gandhiji to return with him to India in 1915. And history was made. “I do not think I can claim a deeper attachment to anyone,” said Gandhiji of Andrews. “I do not own on this earth a closer friend.”