In this feature we help you understand the Hindu place of worship

Symbolism and unwritten codes are woven into the way of life in India. Over time, the symbolism has been forgotten, and so has Sanskrit, the root of many an Indian language. It is important to remember that nothing that is done is without significance, whether it is the posture of an idol, a plant that is worshipped, a particular style of architecture or even a sound. When the significance is known, the gesture or notion takes on so much more meaning. This story highlights the underlying meaning of some of the most common images and icons in India.

Place of Worship

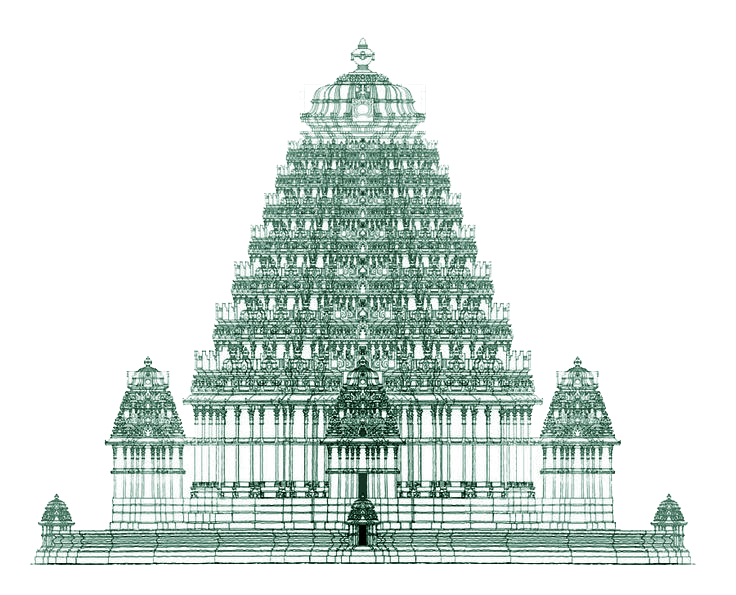

The Hindu temple, like places of worship associated with all religions, is a link between man and God, between the earthly and the divine life. The features of temple architecture symbolise many of the facets of man’s relationship with the Creator.

The gopura, or tower, is at the entrance to any large South Indian temple. It stands for the break between the secular outside and the religious inside, and is much venerated.

The temple being the house of god, a dev-alaya (god’s-house), is in a way His palace. The dwajasthamba (or ceremonial flag post) found opposite the main sanctum in the temple courtyard, flies the insignia of the deity. It is a wooden pole covered with brass or copper sheets, topped by an intricately designed flag. On the base are sculptures of the deities and sometimes their mounts.

Bali-pitam is the pedestal where the offerings for the deity are placed. It is usually next to the dwajasthamba and is made of stone designed like an inverted lotus, on which the footprints of the deity are sometimes carved.

Set in stone

When a person enters the temple, he stamps on the granite step but prays to the granite statue. A story goes that the granite step complained to the sculptor about its lowly position although made from the same block of stone as the idol worshipped in the temple. The sculptor explained that the statue had to go through a lot more pain to be carved intricately and was hence more revered. As a compensation, the first big entrance temple step was granted the wish that people would step over it, not on it. Notice this practice next time you are in a temple!

Sacred stories

The earliest temples in India were in caves or hewn out of rocks. The most sacred part of the temple, the sanctum sanctorum, is called a garbhagriha, literally meaning womb. Directly above it rises the sikara or tower, symbolically lifting a devotee up to the plane of the Gods.

Most of the medium and large temples in India are intricately and ornately decorated. The artwork is breathtaking, but the artistes and artisans remain anonymous.

Most compound walls of temples are painted in distinctive red and white stripes. That is just a way of cueing the passer by that this is holy ground, not to be defiled or desecrated.

Lighting the lamp

You will find lamps lit with oil and with wick on terracotta and brass lamps of many sizes in Indian temples. Light is important symbolically, in all cultures. In India, it enjoys an especially deep significance. Light – as a carefully fostered fire, as a searing flare rising with the sweet smell of camphor, or as a flickering flame in a tiny oil lamp – plays an important part in rituals and worship, both in temples and in homes.

The lamp represents our lives. The oil represents the negative qualities like anger, greed and jealousy. The wick is the ego and the flame represents knowledge. It is the flame of knowledge that burns out the ego till there is no residue of negative qualities left. This is the wish of every Indian while lighting a lamp at an altar or at an inauguration function.

Mantras

You will hear chants of mantras in temples. Mana means mind, Tra comes from trayate, the verb which means ‘cross-over’. So mantras are powerful thoughts and vibrations that help get over the problems of the mind. These days, as we seem to have become Human Doings, it is good to slow down, to become Human Beings again.

Many years ago, the Beatles sang of Shanti and made it a popular mantra. Many hymns and chants in Sanskrit end with a peace chant where the word Shanti, meaning peace, is repeated three times. Om Shanti Shanti Shanti. There is a metre and a tone in which this is chanted. This is because there are three things in life that disturb a person; and to overcome these, peace is asked from each of them.

Peace from Nature and Environment: In ancient days, it meant typhoons and tsunamis, floods and torrents. In today’s world, it could include gadgets which hook and stress us too.

Peace from Others: We need to make this request as we always feel that all problems come from others doing or not doing something.

Peace from One’s Own Heart and Mind: Even if our environment and the people around us encourage peace, our mind, which either dwells on past regrets or future anxiety, is capable of destroying our peace. And hence this special wish, for internal peace.

Keeping in mind the recipients of the three requests, the first Shanti is said aloud, the second a bit softer, and the third softest and drawn out the longest, so that the peace in one’s own heart is focused on.

Making Three Wishes

Here, we share a mantra that is great for humankind. This chant, transliterated from Sanskrit and explained in English, focuses on the universality and oneness of all creation. They contain age-old advice on finding peace, security and happiness.

There is a simple three-pronged wish to welcome all that is enduring and wish away all that is temporary. The chant that encapsulates this is:

Om asatoma satgamaya Lead us from the Unreal to the Real

Tamasoma jyotir gamaya From Darkness to Light

Mrityorma amritam gamaya From Death to Immortality

Om Shanti Shanti Shantihi Peace

Om, lead us from unreality of transitory existence and temporary attachments (to family, possessions and profession) to the lasting reality by strengthening my relationship with the permanent and all-pervading Divine Self in my own heart. (The divine symbol OM is omnipresent in everyday Indian life. Om represents the Ultimate Reality – Brahman.)

Lead us from the Darkness of Ignorance, which leads to self-will and wanting to always have it my way which promotes a separateness between myself and others, to the Light of true spiritual knowledge that there is the same divinity at the core of all, so I may seek more to understand than be understood.

Lead us from the Fear of Death of the body as if it were a permanent death of me, which limits me and causes me sorrow, to the Knowledge of Immortality, claiming that the body dies, but Consciousness, which is the real me, lasts forever. By this I become limitless and eternally free from anxiety and fear.

Peace, Peace, Peace.

This hymn is from the Brhadaranyaka Upanishad and is one of the most ancient hymns of India. Brhadaranyaka means a ‘forest of knowledge’ and Upanishad means literally ‘sitting down near’. The knowledge of these philosophical texts of the Upanishads is said to be gained sitting near a spiritual teacher who has walked the path and communicates to us brilliantly, answering all our questions.

Great work… Highly appreciable writings….