The Red Fort in New Delhi not only has a historical significance but also is the platform from where the Prime Minister of India addresses the nation on the occasion of the Indian Independence Day on August 15 every year. Susan Philip takes us through the history and memorable moments of this imposing fort

The Moghul Emperor Shah Jahan’s name is best associated with the iconic Taj Mahal, as far as the architectural triumphs of his reign go. This graceful monument has transcended the bounds of geography and time as a symbol of the undying nature of love. However, it’s not as commonly known that another edifice which has, over the years, become one of the symbols of Indian Independence, was also built by Shah Jahan, the fifth Emperor in the Moghul Dynasty. We’re talking of the historic Red Fort, from the ramparts of which every Independence Day, the Prime Minister currently in office addresses the nation and makes announcements of national and international importance.

The Moghul Emperor Shah Jahan’s name is best associated with the iconic Taj Mahal, as far as the architectural triumphs of his reign go. This graceful monument has transcended the bounds of geography and time as a symbol of the undying nature of love. However, it’s not as commonly known that another edifice which has, over the years, become one of the symbols of Indian Independence, was also built by Shah Jahan, the fifth Emperor in the Moghul Dynasty. We’re talking of the historic Red Fort, from the ramparts of which every Independence Day, the Prime Minister currently in office addresses the nation and makes announcements of national and international importance.

Painting the Fort Red

The term ‘Red Fort’ may be a bit of a misnomer if we’re to go back to its beginning. It’s certainly red now, and it was assumed that the name came from the red sandstone used in its construction. But historians tell us that it wasn’t always red. At least, not wholly red. Limestone was used along with sandstone, making the edifice red and white, Shah Jahan’s favourite colours. It was the British who painted it entirely red, and called it ‘Red Fort’. The Hindi name Lal Qila is a literal translation of the English name. It was originally known as Qila-e-Mubarak or ‘The Blessed Fort’.

It was intended as a palace, the main residence of the emperor’s family, in the fortified capital named Shahjahanabad after the emperor himself. Built in a style employing elements of Persian, Hindu and other architectural traditions, it was completed in 1639, and remained the main home of the Moghul emperors till 1856.

The massive walls that enclose the complex were witness to myriad dramatic developments down the centuries.

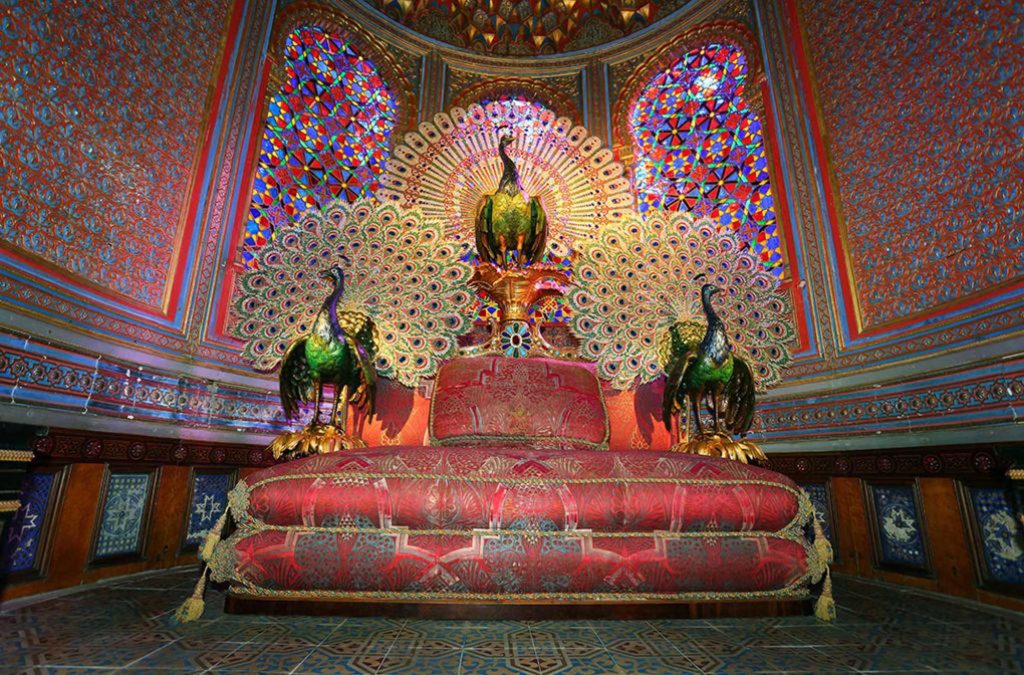

Treasure House

The Qila-e-Mubarak was filled with many treasures, not least of them being the famous Peacock Throne, which was at one time embellished with the even more famous Koh-i-Noor diamond. In 1739, when Nadir Shah of Persia invaded Delhi, his army looted the Qila-e-Mubarak and carried away much of its treasures, including the Peacock Throne and the ‘Mountain of Light’.

House of Resistance

House of Resistance

The Portuguese, the Dutch, the French and the British ‘discovered’ India and began a systematic colonisation plan. The rivalry among the European powers saw the English emerging as the dominant force in due course. As the colonisers disrupted the traditional balance of power involving major and minor royal families, kings, chieftains, landlords and dynastic rule, the Moghuls faded into insignificance. The last holder of the title of emperor, Bahadur Shah Zafar, was ruler in name only. But in the 1850s, he was suddenly thrust into the limelight. He became the figurehead of a resistance movement against the British rule. The idea was to overthrow the foreign power and establish an Indian government with Bahadur Shah as its nominal head.

What is now known as the First War of Independence in 1857 gave the British East India Company a shock, but it ultimately managed to put down the resistance. In the process, the Red Fort, as the home of the emperor, was vandalised. Many of its unique architectural features were destroyed or commandeered for uses other than what was intended, damaging the majesty of the building.

In 1858, the British conducted Bahadur Shah Zafar’s trial within the walls of the Red Fort and sent him into exile in present-day Myanmar. There, the frail old man died a lonely death and was interred in an unmarked grave.

The 1857 war triggered far-reaching political changes. India was made a part of the British Empire, and the administration was no longer in the hands of the East India Company. Delhi was named the capital, replacing Calcutta, as Kolkata was then known. The association of the Red Fort with the ruling power was subtly turned to its advantage by the British when, after the Coronation Durbar held to welcome Britain’s newly crowned King George V to India, a Jharoka Darshan or audience from the balcony was arranged where the monarch and his wife Queen Mary made an appearance on one of the balconies of the Fort to greet the public, symbolically underlining the fact that the British Emperor had replaced the Moghul Emperor.

But in the minds of a people increasingly determined to secure self-rule, Swarajya, the Red Fort stood out as a structure intrinsically Indian in an anglicised environment, a symbol of their aspiration for freedom from the foreign yoke. For the British too, it retained its flavour as a centre of dissidence.

Raising the Flag of Independence

Around a century later, at the time of World War II, Netaji Subash Chandra Bose, who formed the Indian National Army (INA) with the idea of evicting the British from India, visited the shrine that had come up at Bahadur Shah’s grave, and gave his famous ‘Chalo Dilli’ (Let’s march to Delhi) call, invoking the emperor, the Red Fort and all it had come to stand for. Later, after the INA was demolished, the British decided to make examples of three of its top men and incarcerated them in the Red Fort before holding a public trial. But memories of the last Moghul emperor’s trial resurfaced, and the move only served to fan a public outcry.

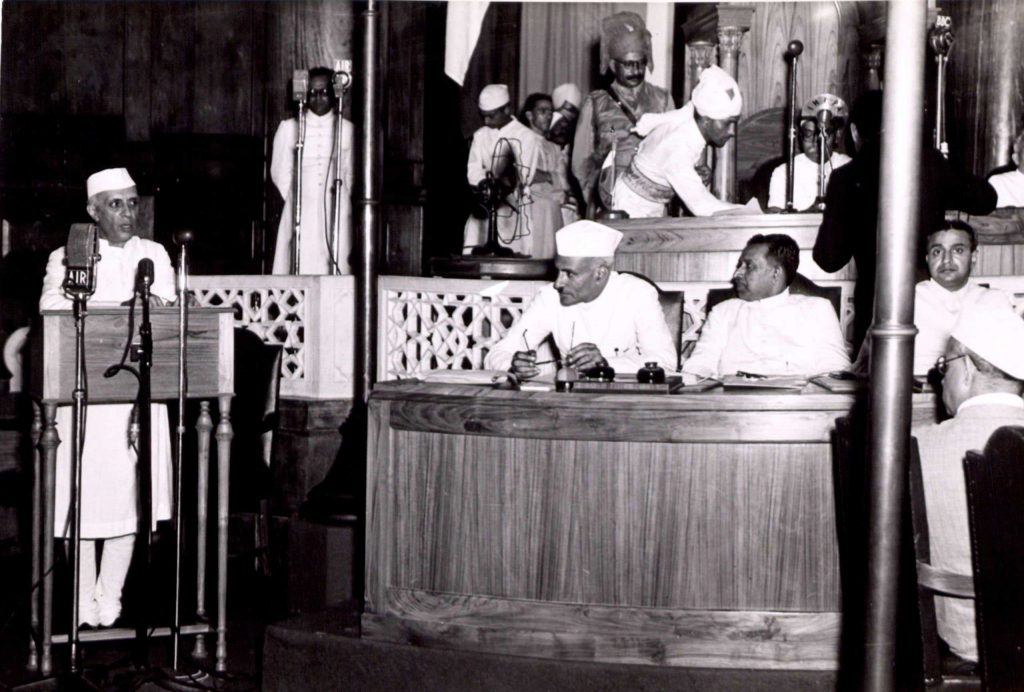

The Red Fort came to symbolise India’s struggle for independence, and the association was complete when, on the morning of August 15, after his soul-stirring ‘Tryst with Destiny’ speech in the Parliament at the stroke of the midnight hour, India’s first Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru hoisted the tricolour on the ramparts of the Red Fort and addressed the new-born nation for the first time. That’s a tradition which has continued down the years.

A Hallowed Tradition

Every year, as the anniversary of Independence Day approaches, the Red Fort is spruced up and decorated. Top-level security measures are mounted. The political and business elite gather at Lahori Gate. Amidst pomp and splendour, visiting dignitaries are escorted to their appointed seats. And all eyes, ears and television cameras are trained on the Prime Minister, who, echoing the events on that first Independence Day, unfurls the National Flag and then addresses the nation.

The Lahori Gate

The Lahori Gate, the current main entrance to the Red Fort, is the place from where the Prime Minister traditionally delivers the Independence Day address. The location is significant. From the Throne Balcony in the Hall of Audience where the emperor once heard the grievances of the people, there’s a direct path to the Lahori Gate, and from the gate, the road runs ruler-straight into the main thoroughfare of the city as it was then, architecturally symbolising the arterial connection of the ruler with the people.

Fourteen people have been Prime Ministers of India so far, not counting Gulzarilal Nanda, who held office twice briefly, to fill the gap between the untimely deaths of two incumbents and the election of their successors. While some of them held office for two terms, some did not complete even a year in office, and they could not address the nation from the Red Fort because an Independence Day anniversary did not fall within their term. Among those who spoke from the Red Fort, some were powerful orators, holding their audience captive with rhetoric. Some were soft-spoken, reading from prepared texts. Some were prosaic and to-the-point. Others were eloquent, even poetic. But they’ve all delivered important messages from the ramparts of the Lal Qila on the morning of every August 15 since 1947.

From dreams to despair, from the poetic to the prosaic, the scarred walls of the Red Fort have seen and heard it all. What tales they could tell us, if only they could talk!

From dreams to despair, from the poetic to the prosaic, the scarred walls of the Red Fort have seen and heard it all. What tales they could tell us, if only they could talk!