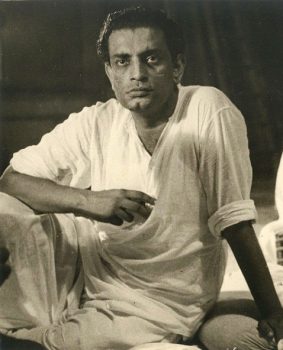

Spanish Filmmaker Alfredo de Braganza on Satyajit Ray, one of India’s finest filmmakers and an Academy Award Winner for Lifetime Achievement

“Villains bore me,” Satyajit Ray (Calcutta 1921-1992) wrote once. In Camus’s The Plague (French title “La Peste”), a character says, “I understand everyone, so I judge no one”. Ray made us understand. In the sparest and the most refined of cinematic idioms, he gave us a world. If Joyce captured a man in full through the relentless description and analysis of a day in Dublin, Ray’s films are delicate vignettes sculpted in time recording an entire culture. The New Yorker film critic Pauline Kael said about him, “Ray sees life itself as basically good, no matter how bad it is.”

On a business trip to London in 1950, Satyajit Ray watched Vittorio de Sica’s Bicycle Thieves more than a dozen times. On the ship back to India, he wrote a screenplay for his first film, Pather Panchali (“Song of the Little Road”). It became the first movie from independent India to attract major international critical attention and won the “Best Human Document” at the 1956 Cannes Film Festival, establishing Satyajit Ray as a major international filmmaker. Even today it is considered one of the greatest films ever made.

Forget the technical jargon of montage, mise-en-scène, fade-outs and jump cuts, Ray performed, better than any other Indian, the basic duty of a filmmaker. He communicated. He touched. The fun and games of Durga and Apu, the caring and sharing of the siblings, the candyman, the kittens, the rain dance and the loss of a sister, and the inability of Apu to comprehend its enormity as he brushes his teeth without his sister Durga by his side. This film is about childhood but made through the filtered vision of an adult looking back, which makes it that much more nuanced and philosophical.

Pather Panchali was followed by two films that continued the tale of Apu’s life: Aparajito (“The Unvanquished”) in 1956 and Apur Sansar (“The World of Apu”) in 1959. The three films are together known as The Apu Trilogy. Whether it is the smile of a child staring at the pompous village shopkeeper-teacher or the tragedy of a mother who has lost her young daughter, emotions are articulated without words and are all the more searing for that. You don’t need subtitles to sympathise with these people, you live alongside their feelings; it is all about visuals held together by silences and sounds to create feelings that are abidingly haunting.

If we take a clinical eye to Apu’s story, nothing much happens to him that is out of the ordinary. His lower middle-class life is but a basis point in the statistical percentages of social studies. But Ray makes him Everyman; you see him grow from birth to fatherhood, and all you want is that he should be happy. His quest becomes yours. The important thing is not that he is a villager, not that he is a Bengali, but that he is a human being, a person, and that is the universality of the film.

For a viewer who had lived on a healthy diet of Hollywood blockbusters or mega-budget Bollywood flicks and regards cinema as an escape, Pather Panchali can become too real for comfort. This viewer can sense the slow rhythm from the beginning, not understanding the subtle emotions and can get bogged down even by the poverty and relentlessly tragic mood. In my opinion, the most important criticism which we can make of Ray is that he believes naively that people are fundamentally good and that his films are too well crafted in contrast, for example, to the raw passion of Ritwik Ghatak and his spontaneous and stubborn frames. Like every giant, Ray suffered attacks from intellectual midgets, some of whom whined that the only reason he was so well received in the West was because of the negative picture his film showed of poverty in India. This is, of course, rubbish. Certainly the people in his films were poor and their lives were conditioned by that poverty. But poverty, in one degree or another, is a fact of life for every large part of the world’s population. The people in Pather Panchali are engaged in the struggle to survive, but it does not impair their humanity!

I personally find a link between Ray’s film and a “magic” scene from Guiseppe Tornatore’s Cinema Paradiso when the young boy Toto is fascinated as Alfredo (his projectionist friend) inclines the projector and lets the moving image travel out of the theatre over the wall of the town square. Martin Scorsese once said, “With Ray’s films you became attached to the culture through the people”. Watching Pather Panchali, the experience is not about acting, camera frame, music (by Ravi Shankar), editing or sound. It is about more than that: an unforgettable movie magic experience; a ray of light to your consciousness.

Alfredo de Braganza (Spain) is an independent filmmaker. He is regarded as the first Spanish person to shoot an entire feature film on celluloid in India. He has made a Tamil feature film, Maayan The Fisherman, and a documentary feature in Hindi shot in the Himalayas, Smoking Babas Holy Men of India.