…And he will take something of India with him. a noteworthy aspect of Indians’ migration is that they took with them Several cultural facets from the subcontinent, which are rooted in the daily lives of people in other countries

The Indian subcontinent is, geographically speaking, an ‘insulated’ area. The Himalayas in the north and the Arabian Sea, Bay of Bengal and Indian Ocean in the south should logically have made it difficult for anyone to get into or out of the region, at least till the advent of modern modes of travel. Of course, with the opening up of trade and the subsequent quest for empires, employment and employees, there have been exoduses of various types from India to the world. But what’s interesting is that this is by no means a ‘modern’ phenomenon. Even as long ago as the third millennium BC, groups of people have been migrating from India for one reason or another.

Ancient Hindu texts advice against ‘crossing the seas’ – foreign travel, in other words. Even so, the great sage Agasthya is believed to have visited south-east Asian countries like Cambodia and Siam (Thailand). And, according to legend, sage Koudinya set sail from India with the dream of establishing an empire in the east. When his ship neared the Cambodian coast, it was attacked by a group led by the daughter of the local king. Koudinya fired arrows from the bow he had brought from an Indian temple, and established his superiority. He married the princess and founded the wealthy Funan Empire.

Agasthya and Koudinya were not exceptions to the rule. Trade was a great pull across the waters for ancient Indians. They took with them their culture and

their religious beliefs, and these took root in new lands where they prospered, albeit with local adaptations.

Following the dictum of Emperor Ashoka, groups of Buddhist missionaries also left India to spread the Buddha’s teachings. They went to China, Japan, Sri Lanka and to Southeast Asia. And much later, Muslim traders from Gujarat took Islam to Indonesia.

There were overland trade routes too, to the Middle East and Europe, particularly Rome. Interestingly, the Romanis, who are intrinsically nomadic, popularly known as ‘gypsies’ in countries across Europe today, trace their origins to large groups of people who left the north-western region of India around 1,500 years ago. They went to the Middle East and Africa and also to various parts of Europe. Their language still bears some similarities to those spoken in northern India.

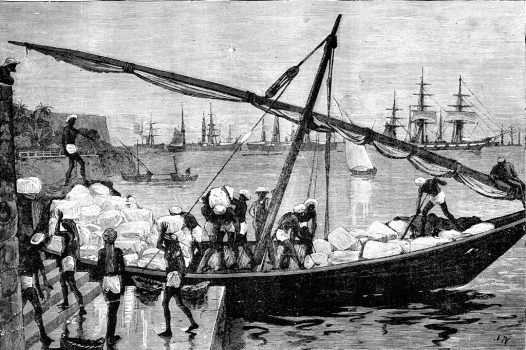

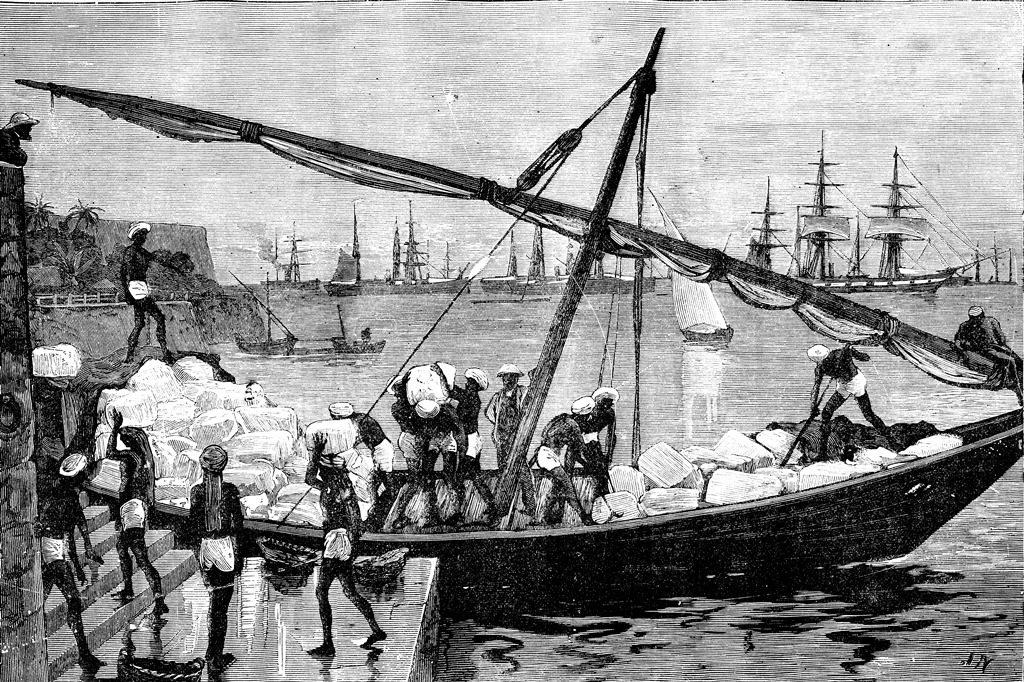

As years went by, the profile of those who left India’s shores changed. Apart from traders, there were financiers, like the Chettiars of Tamil Nadu. There were businessmen, like the Sindhis who had textile and jewellery enterprises. Whole families settled down in countries with which they had commercial links, so that they could do even better. They went to countries as distant as Spain and the United Kingdom.

In 1833, slavery was abolished in Britain, and other countries followed suit. The availability of cheap labour from Africa came to an abrupt end. Britain got the idea of using indentured labourers from India to work in cotton and sugarcane fields in the Caribbean and other colonies. Other countries followed Britain’s lead in their own colonies too. And then there were the teachers, the doctors, the nurses and of course the IT professionals, who left in search of pastures greener.

Quite often, the early migrants were mostly men. They found spaces for themselves in the new countries they went to, and managed as best as they could. When women were able to accompany their menfolk, things were a little easier. And it was mainly the women who clung to the customs and rituals, the food they had grown up with, and tried to pass them on to the next generations. In some instances, these customs are still practised with fervour on foreign shores, whereas in India itself, they may not be as strictly or enthusiastically observed.

Whatever the reason for the migrations that happened down the ages, people from India have left indelible marks on the psyche of their adopted countries. And the beauty of it is that they did not do it by violent or coercive means. They did it with soft power! Indian Diaspora were welcomed wherever they went because they weren’t interested in establishing political supremacy, but contributed to the economy. Indian food, customs, festivals, words, names, architecture, literature, music and dance forms, and religious beliefs found their way into the daily lives of the people in far-away places. And those facets of foreign lands will remain forever Indian.

Fun facts

- Indonesia’s Airlines is named Garuda – the vehicle of the Hindu God Vishnu.

- Sanskrit was Cambodia’s language for administration till the 14th century.

- Indrapura, Amaravati and Panduranga are cities in Vietnam.

- Svarga and mantri are examples of Malay words with Indian roots. They mean the same as their Indian versions – heaven and minister.

- Wayung (left) Indonesia’s famous puppet theatre, is very like the Tholu Bommalatta of Andhra Pradesh.

- The bitter gourd, okra, mango, betel nut, jackfruit and tamarind are some native Indian plants that were transplanted and flourished on foreign shores.

- In Amharic, Ethiopia’s national language, Surat means tobacco – a reference to the city of that name in Gujarat from where it

was first brought.

Fusion Food

- It is well known that Indians can’t do without spices. Wherever they migrated, they carried spice boxes with them, and these ‘exotic’ flavours found their way into the foods of the lands they settled in. Various types of ‘curry’ teamed with rice are staple meals in Southeast Asian countries, and popular in the West Indies and Africa too.

- Debe, a Caribbean town, is known for the Debe Double, basically a fried portion of dough called barra (could it be a take on the vada?) served with a chick peas and pepper sauce. It was originally a single serving, a breakfast dish to sustain Indian plantation workers. But it wasn’t filling enough, and the workers asked for double servings, so it metamorphosed into a sandwich-type presentation and came to be known as the Debe Double.

- The Bunny Chow, a local delicacy in Durban, has nothing to do with rabbits, or their food. It has Indian roots, with the word ‘bunny’ being a corruption of baniya, a Gujarati business community. It is thought to have evolved from an innovative way Indians devised to carry packed or take-away lunches in the absence of containers – hollow out a loaf of bread (a substitute for the roti) and fill it with a vegetable side-dish. In course of time, meat and beans were used as fillings. It is now served with a side of grated carrots and other vegetables.

- Other foreign adaptations of Indian favourites, old and new, include kedgeree (originally from kitchdi, a dish of rice and lentils), almond brittle (the ubiquitous peanut chikki), turmeric latte (from the Ayurvedic therapeutic concoction of warm milk, turmeric and a dash of pepper), Ethiopia’s injera, a close cousin of South India’s dosa, Lisbon’s chicken chamuchas (a take on samosas) and Britain’s favourite chicken tikka masala.