Even as Indians have embraced digital forms of communication with fervour, the Indian Postal Service continues to holds its pride of place as the lifeline of the country. We take a look at the evolution of the country’s postal service – from horse-driven deliveries to the friendly neighbourhood postman.

India’s Post Office is often regarded as a legacy of the Raj, but postal systems developed in India long before the arrival of the British. The Shatapatha Brahmana, a text describing Vedic ritual and history written around 700 BCE, refers to the king’s courier, the palagana, who is ‘despatched on his way’, and the 3rd century BCE Artha Shastra, a treatise on statecraft, economic policy and military strategy, mentions systems for collecting information and revenue data on behalf of the king, noting ‘a messenger of middle quality shall receive 10 panas for each yojana he travels; and twice as much when he travels from 10 to 100 yojanas.’

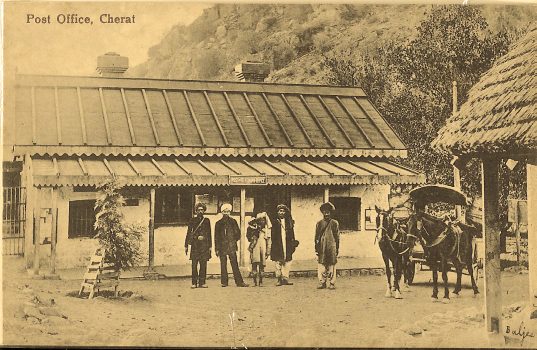

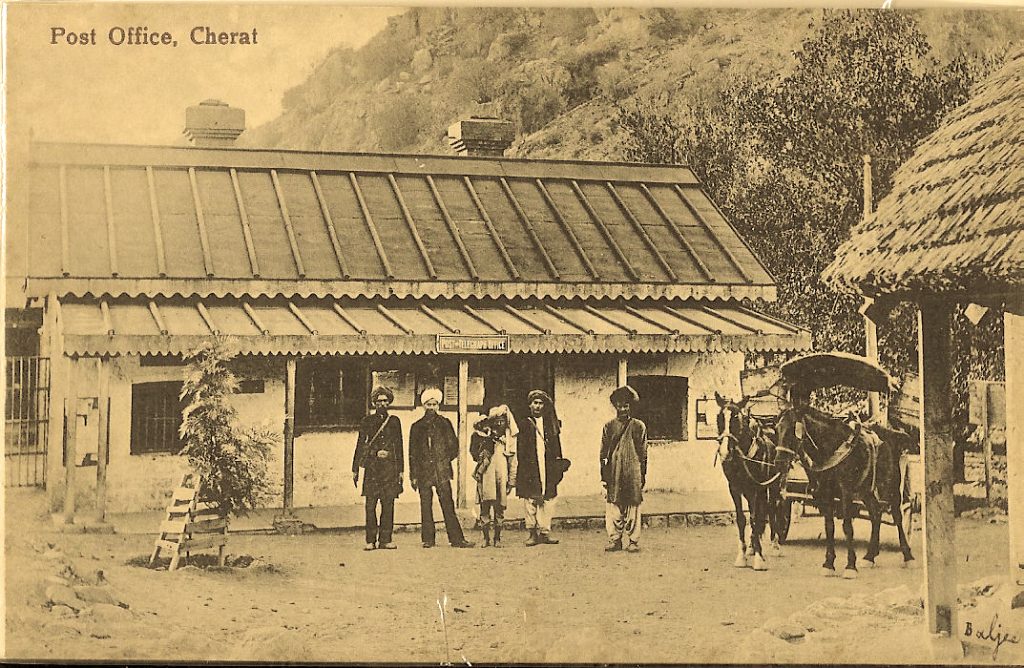

Messages were carried by runners on foot, and routes evolved for the carriage of despatches. Following the conquest of Sindh by Muhammad bin Qasim in the 8th century CE, swift horse messengers were established in the province; and the rulers of the 13th century Mamluk dynasty created a messenger post system of runners on foot and horse to gather information about developments within their state. The Venetian explorer Marco Polo noted the presence of ‘Horse-Post-Houses’ at 25-mile stages on all the principle highways leading to different provinces, with horses standing ready for messengers, and the courier system was to be developed further by Babur, the first Mughal emperor, as part of his intelligence system. He constructed watchtowers to ensure safety along the routes, and ensured couriers and grooms were paid, and feed supplied for horses.

By the 16th century, communications routed along the highways between Bengal and Sindh were supported by hundreds of serais, stopovers built along the roads as rest houses for pilgrims and traders. These served as staging posts for couriers where horses, camels and runners were kept in readiness for the speedy onward despatch of messages. Under Sher Shah and later Akbar these became dak-caukis (literally ‘mail check-post’), stations from which messengers operated in exceptionally fast relays. The Mughals also used homing pigeons to carry messages.

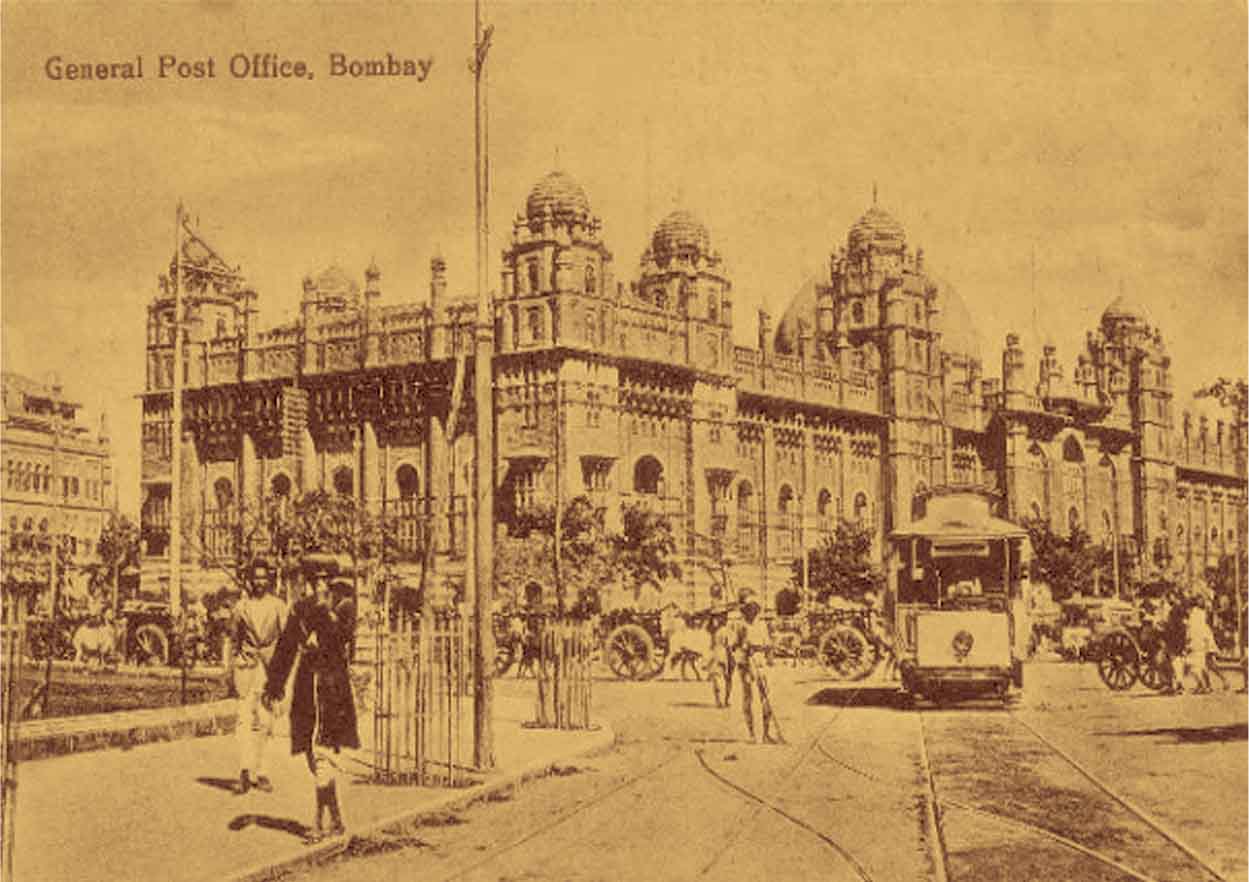

As early as 1688, when its focus was still on trade, not the building of an empire, the East India Company opened a post office in Bombay, and then in Calcutta and Madras, but it would remain difficult for officials to send letters any great distance. A regular postal system was first introduced by Lord Clive in 1766, and the zamindars (landholders) along the various routes were held responsible for the supply of runners to carry the mail. Officials complained that ‘… frequent miscarriages of packets to and from Madras [occur], without possibility of tracing the cause, not knowing the stages where they do happen’. Communications were ‘tardy’ as no allowance was made for ‘passing the rivers’ and they demanded small boats be stationed as required.

As early as 1688, when its focus was still on trade, not the building of an empire, the East India Company opened a post office in Bombay, and then in Calcutta and Madras, but it would remain difficult for officials to send letters any great distance. A regular postal system was first introduced by Lord Clive in 1766, and the zamindars (landholders) along the various routes were held responsible for the supply of runners to carry the mail. Officials complained that ‘… frequent miscarriages of packets to and from Madras [occur], without possibility of tracing the cause, not knowing the stages where they do happen’. Communications were ‘tardy’ as no allowance was made for ‘passing the rivers’ and they demanded small boats be stationed as required.

Under Warren Hastings, the services were expanded and made available for private as well as official communications. In 1774 the details of a regularised system were laid down, and rates of postage established: a fee of two annas per 100 miles. Post office departments were established in Calcutta in 1774, in Madras in 1778, and in Bombay in 1792. Even so, there was no central authority to secure the cooperation of the postal officials in different districts, or to maintain uniformity of procedure. Private dak systems existed everywhere, whilst the local Indian rulers maintained their own courier systems.

In 1837 the Indian Post Office was established, and the then Governor General assumed the exclusive right to convey letters by post within the territories governed by the East India Company – for all its seemingly benign intent, this was, of course, part of the Company’s structure of power. The Imperial Post controlled all the main routes and large offices, and the District Post managed rural services, pioneering postal facilities in backward rural tracts.

In 1837 the Indian Post Office was established, and the then Governor General assumed the exclusive right to convey letters by post within the territories governed by the East India Company – for all its seemingly benign intent, this was, of course, part of the Company’s structure of power. The Imperial Post controlled all the main routes and large offices, and the District Post managed rural services, pioneering postal facilities in backward rural tracts.

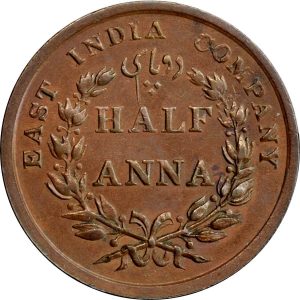

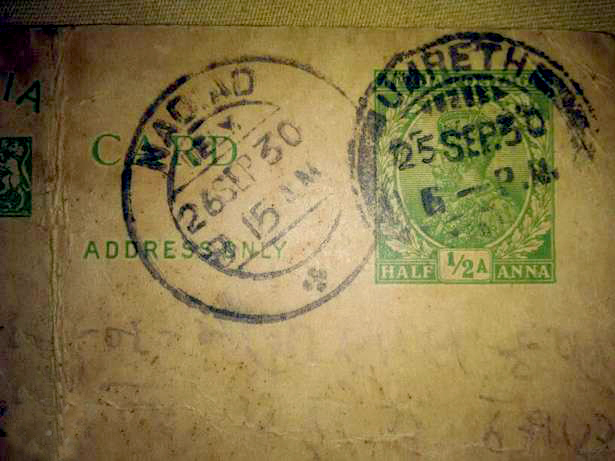

By the mid-19th century it was apparent that a uniform rate of postage, irrespective of distance, was required, as was the need for prepayment by means of stamps. Until then it required a lengthy consultation with a daunting book of tables to establish the postal rates for a letter from, say, Madras to Lucknow, but from 1855 a letter could be sent anywhere from anywhere in India for half an anna. Compulsory prepayment meant that letters could not just be read by the recipients then refused, leaving the both the sender and recipient satisfied but the Post Office without revenue – a common practice, by account.

By the mid-19th century it was apparent that a uniform rate of postage, irrespective of distance, was required, as was the need for prepayment by means of stamps. Until then it required a lengthy consultation with a daunting book of tables to establish the postal rates for a letter from, say, Madras to Lucknow, but from 1855 a letter could be sent anywhere from anywhere in India for half an anna. Compulsory prepayment meant that letters could not just be read by the recipients then refused, leaving the both the sender and recipient satisfied but the Post Office without revenue – a common practice, by account. At the same time, the rates and conveyance for parcel post, which had its origins in the old ‘bhangy post’, the name derived from the bhangy or bamboo stick with parcels on either end that carriers balanced on their shoulders, were laid down with the railways, but only after much wrangling between the Post Office and the railway companies. Post Office officials, it was said, seemed to think that railways had been invented only for the conveyance of mail, whilst the railways regarded the Post Office as a nuisance, and its officials as thieves.

At the same time, the rates and conveyance for parcel post, which had its origins in the old ‘bhangy post’, the name derived from the bhangy or bamboo stick with parcels on either end that carriers balanced on their shoulders, were laid down with the railways, but only after much wrangling between the Post Office and the railway companies. Post Office officials, it was said, seemed to think that railways had been invented only for the conveyance of mail, whilst the railways regarded the Post Office as a nuisance, and its officials as thieves.

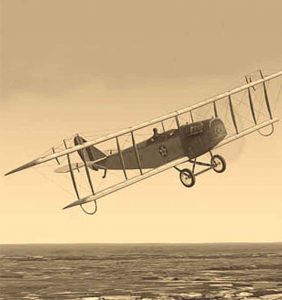

The postal service developed into an extensive network of post offices and letterboxes, and the volume of mail moved by the system increased relentlessly, doubling from 224,000 in 1855 to 556,000 in 1866, then again by 1871. New services emerged. The Post Office took over the management and issue of money orders, and Post Office savings banks opened across the country. The telegraph was introduced in 1850 and the first telephone exchanges in the 1880s, both part of the postal service before becoming separate departments. The world’s first official airmail flight took place in India in 1911 when a French pilot carried mail a distance of 11 miles (18 km) across the Ganges.

The dak-wallah – the postman – became the branch of public service in closest contact with the people. He was earnest and dutiful, undergoing perilous journeys through difficult terrain to reach his destination. Local knowledge was a necessity; letters would bear the name of the person but no indication of the place of delivery. One such example was addressed only ‘To the sacred feet of the most worshipful, the most respected brother, Guru Pershad Singh’. If he read no English, the postman would scrawl the name of the recipient in the vernacular on the back of an envelope, or a description. Hence Sir John Stevens, a judge in the Calcutta High Court, received letters with the words ‘Old Stevens Sahib’ on the back, which distinguished him from his younger colleague, Mr Justice Stephens.

The dak-wallah – the postman – became the branch of public service in closest contact with the people. He was earnest and dutiful, undergoing perilous journeys through difficult terrain to reach his destination. Local knowledge was a necessity; letters would bear the name of the person but no indication of the place of delivery. One such example was addressed only ‘To the sacred feet of the most worshipful, the most respected brother, Guru Pershad Singh’. If he read no English, the postman would scrawl the name of the recipient in the vernacular on the back of an envelope, or a description. Hence Sir John Stevens, a judge in the Calcutta High Court, received letters with the words ‘Old Stevens Sahib’ on the back, which distinguished him from his younger colleague, Mr Justice Stephens.

The postman was an integral part of the lives of communities, a relationship that was not without conflict as RK Narayan’s short story ‘The Missing Mail’ (1947) portrays. In this the genial postman, who brings news of marriage offers, new grandchildren and job interviews, makes a decision to delay the delivery of a telegram about a death in the family to ensure that a forthcoming marriage is not postponed. In the 1977 film Palkon ki Chhaon Mein, the life of the hero is transformed when he is mistaken for a candidate for the job of a postman and taking the post, discovers friendship, drama and love while delivering the post to the villagers on his round.

The Indian postal service grew sevenfold after Independence, and is now the largest postal network in the world. But the landscape is changing – modern India has embraced digital communications and leads the world in their implementation. Only ten years ago, there was a tactile quality to the post, with mail sent in a range of materials that included wax paper, cloth paper and paper reinforced with cotton. In the age of the Internet and instant messaging, this now seems quaint, just as the closure of the country’s last telegraph office in 2013 was marked by the despatch of one last telegram, sent to Rahul Gandhi.

Even so, its branch infrastructure of 155,000 post offices makes the Indian Post Office larger than the entire network of all the commercial banks of the country and, significantly, 90 per cent of the network caters to rural areas where it is a lifeline both familiar and trusted. The quantity of mail delivered year on year has started to decrease, but the postal department has moved beyond its traditional function, delivering a range of financial services include savings and deposit account services and insurance to over 150 million people. It is responsible for disbursing government payments and social benefit schemes, provides money orders, sells foreign currency and collects payments on behalf of service providers. It has been leveraged by e-commerce companies such as Flipkart and Amazon, delivering parcels to places where courier companies do not operate.

Even so, its branch infrastructure of 155,000 post offices makes the Indian Post Office larger than the entire network of all the commercial banks of the country and, significantly, 90 per cent of the network caters to rural areas where it is a lifeline both familiar and trusted. The quantity of mail delivered year on year has started to decrease, but the postal department has moved beyond its traditional function, delivering a range of financial services include savings and deposit account services and insurance to over 150 million people. It is responsible for disbursing government payments and social benefit schemes, provides money orders, sells foreign currency and collects payments on behalf of service providers. It has been leveraged by e-commerce companies such as Flipkart and Amazon, delivering parcels to places where courier companies do not operate.

For example, places such as Hikkim. Located in this remote village in Himachal Pradesh, 15,000 feet above sea level, is India’s highest post office. From Hikkim, the mail is taken every morning on foot to the town of Kaza, then by bus to Reckong Peo, on to Shimla and then to Kalka by train where it is again put on a bus and driven to Delhi for sorting. The spirit of the dak-wallah lives on.