Early life

I grew up in New York State and when I came to India at age seven, I was already a snake catcher. My mother was an unusual woman who was very happy to let me bring snakes home (they were non-venomous in New York). She’d ask if we could keep them instead of the usual reaction of “get that thing out of here!”

Moving to India was exciting. We were in Juhu, in then Bombay, which was just beginning to be colonised by movie stars. My stepfather Rama Chattopadhyay owned India’s first colour processing lab for movies, so we were in the centre of what became Bollywood. We’d go fishing in Powai Lake next to actor Shammi Kapoor and chat with him.

School, college and beyond

I spent eight years of boarding school in Ooty and then in Kodaikanal. The Western Ghats really helped me understand forests. I went out with local hunters (in those days, it was hunting and not catching). I enjoyed getting out in the field and learning a lot from the local people.

Then when I was graduating from high school, I read all the American college catalogues to choose one. I chose Wyoming University only because it said Wyoming has

more deer than people! There, I spent more of my time hunting, fishing and goofing off. But my love and interest for snakes remained.

I dropped out after managing a year there and went to Florida, to the Miami Serpentarium, then the biggest venom production centre in the world. It was run by Bill Haast, whom I had read about in my schooldays and had actually written to in the 1950s. He said if you’re ever in America, come visit us, and that’s just what I did. I worked with them for two years before the Vietnam War caught up and I was drafted into the army.

The birth of Snake Park

My experience in America planted the idea of setting up a snake park in India. It is the land of snakes, yet we have so many misbeliefs and misconceptions. I was a proselytiser for snakes, and that’s how the Madras Snake Park was set up through a series of wonderful coincidences and great people. The first year had a million people coming in. Even at only 25 paise a ticket, it was enough to keep things rolling.

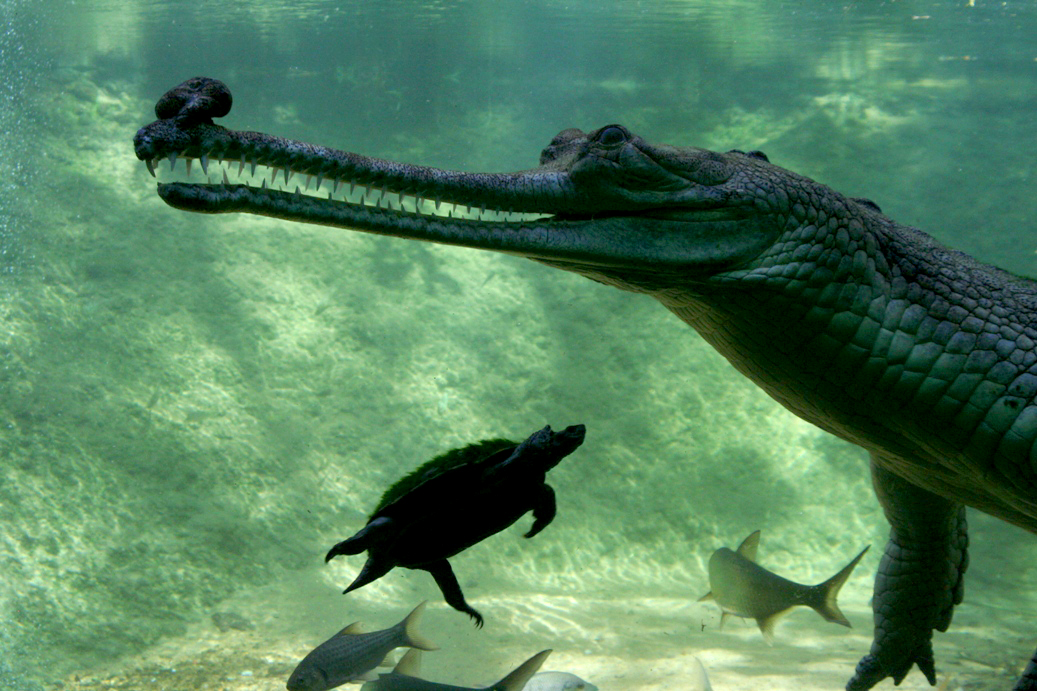

I then wanted a reptile park but the space was tiny. We’d need a big place to keep big animals like crocodiles. I can imagine how odd my ideas sounded to people; but they caught on, and with the help of organisations like WWF, the Madras Crocodile Bank was set up. We started with 14 crocodiles and have ended up with 2,500 today. I wonder if they’re rabbits or crocodiles!

The global snakebite initiative

Recent statistics in India show almost 50,000 men, women and children die from snakebite, of which 98% are in rural areas. It shocked the heck out of us. The unknown statistic is how many survive snakebites but lose a limb or are completely incapacitated. Generally, males are bitten, and they’re often the primary breadwinners of their families, so it’s a very serious thing for rural India in particular.

As a result, almost everything we’re doing now on the Global Snakebite Initiative is aimed at the rural community and labourers. We launched the programme in Tirunelveli in Tamil Nadu in September, tying up with the forest, fire and police departments, and a large group of students. We made a template backed up with a couple of videos to break down the problems; very simple videos that can be translated into different languages.

This awareness campaign targeted a couple of things. The first is how to avoid snakes, by keeping places clean and keeping rats out of the house. The second is what to do if you’re bitten. The focus is on getting to a hospital and being administered an anti-venom injection. The anti-venom manufacturers were very pleased to hear this, so they – and the Infosys Foundation – doled out enough money to make the films.

The healthcare company USV also gave Crocodile Bank a CSR grant to spread this campaign to seven states which have been identified as the “most snake-bitten states”. The sky is the limit after that.

The problems with anti-venom

There isn’t a map yet of which state districts have the most snakebites, and which hospitals get the most patients who require treatment for snakebites. The anti-venom available could also be of better quality. Along with the Indian Council of Medical Research and the Department of Biotechnology in Delhi, we’re trying to help anti-venom manufacturers improve their product.

But this isn’t the only problem! Here’s an example: the Russell’s viper is a snake that causes most of the deaths in India because it’s big, has long fangs and very toxic venom. However, the venom from this viper in South India is different from the venom of the Russell’s viper from North India. Why? Maybe they’re genetically different because of the food they eat.

The cooperative we set up to produce anti-venom gets

all its snakes from one district in Tamil Nadu – Kanchipuram – which is then sent to anti-venom manufacturers across

the country.

Unfortunately, the anti-venom produced from a South Indian Russell’s viper might not work against the venom from a North Indian Russell’s viper. We now need to take different samples of venom from across the country.

Awareness is key

The snakebite problem is a dynamic combination of conservation, ecology, human welfare and medical health. We need to live with snakes. In rural India, 20–30% of crops are eaten by rodents, and snakes keep this population in check. So all we need is awareness on how to live with them in the right way.

A lot of the things we have achieved is through support from big companies in their CSR programmes. Constant awareness in remote areas can reduce snakebite deaths by 50% in a year if we just keep at it.

Diseases in developing countries kill thousands of people around the world, and the World Health Organisation has now recognised snakebite as one of these problems, giving impetus to our programmes to get government departments involved too. If you add up the number of people killed by other animals every year, that number is just a fraction of those killed by snakebites. Also, consider the cost to the economy. Snakebite deaths cost the economy of Sri Lanka

$10 million annually. A country like India will have a far higher number.

People are attracted to snakes, whether positively or negatively. They want to hear about snakes, and they want to know about these problems. This is a good wicket for us to start from.