Telling stories takes on a new meaning in India as it is becomes an art form composed of narration, poetry, music, drama, dance and philosophy – we take a look at the main forms of narrative storytelling

Across India, traditional stories have entertained and instructed people for thousands of years. The stories passed down through the centuries have been received and retold in many different forms, shaping India’s immense cultural heritage. The great myths and legends were recalled through retellings of the Ramayana and Mahabharata; the Puranas recounted the stories of the deities; and folk tales about kings and queens, noble warriors, wise sages, brave hunters and clever animals offered the listeners lessons in morality. These tales, epic and folk, sacred and secular, were learnt by heart and brought to life by successive generations of itinerant bards and performers. To this day, storytelling is frequently a composite art form, composed of narration, poetry, music, drama, dance and philosophy. Tales are narrated to a musical or percussion accompaniment and highly stylised dance-dramas are amongst the most iconic of India’s performing arts. In this article we focus on the main types of narrative storytelling in India.

Classical Forms of Storytelling

Several oral traditions took their inspiration from the performances of devotees in the temples or poets at the courts and have evolved into highly refined forms of storytelling. Harikatha, meaning ‘the telling of the stories of God’, is a sophisticated style of storytelling from Tamil Nadu that explores religious themes, usually the life of a saint or a story from an Indian epic. It is performed in sabhas (auditoriums), marriage halls and temples by harikatha bhagavathars, or experts, whose devotion to the art of storytelling has been honed by years of practice. The training is rigorous: a bhagavathar must speak several Indian languages, quote thousands of religious verses and sing in both classical and folk traditions. Moreover, it is essential that the bhagavathar has the dramatic prowess to enrapture the audience, to instruct and to entertain with comment and anecdote.

Watch a harikatha rendition by Vishaka Hari

Kirtan is a devotional form of storytelling that is popular in Maharashtra. The kirtankars tell stories to the accompaniment of musical instruments in a call-and-response style song or chant, with different singers reciting or describing the story. They express loving devotion to a deity or discuss spiritual ideas. The audience is encouraged to repeat the chant or reply to the call of the singer.

Watch Krishna Das present a kirtan

Chakyar koothu, from Kerala, is performed only in temples and is a form of discursive monologue with emphasis on gesture on facial expression. Although affecting a mannered style of storytelling, the narrator often incorporates commentary on current social and political events and directs comments and insults at the audience.

Watch a chakyar koothu performance by Sreehari M Chakyar

Folk Forms of Storytelling

For the people of rural India, the country’s folklore and legends came alive in the village square. There are still numerous forms of traditional theatre staged in the open in performances that are steeped in ritual. Often the plays begin at dusk and are performed throughout the night. There are no sets, props are minimal, but the actors wear resplendent costumes, head-dresses and face paints.

Yakshagana, prevalent in Karnataka, literally means the song (gana) of a yaksha. According to Hindu, Jain and Buddhist texts, yakshas were nature spirits associated with the woods, mountains, lakes and wilderness. Yakshagana performances begin at dusk with the beating of drums for up to an hour before the actors emerge. The narrator is backed by musicians playing traditional instruments, and the actors interpret the story as it is being narrated. All the components of yakshagana, music, dance and dialogue, are improvised and it is not uncommon for actors to get into philosophical debates or arguments without going out of the persona of the character being enacted.

Watch a yakshagana performance

Therukoothu, meaning ‘street drama’, is from Tamil Nadu. Stories told with song and dance from the Mahabharata and the Ramayana form the basis of therukoothu performances, but it also borrows heavily from other historic Tamil texts. Usually it is performed only by male artists, dressing up as both male and female characters.

Watch a therukoothu performance

Another ancient storytelling form from Tamil Nadu is the folk music genre villu paattu, named after the tautly stretched long bow that forms the main instrument of percussion. Villu Paattu intersperses music with storytelling, narrating a range of stories from the mythological to current social concerns, and is usually played at temple festivals.

Watch a villu paatu rendition by Subbu Arumugam

The most popular form of entertainment in the villages and towns of northern India, before the advent of Bollywood, nautanki still commands huge audiences. It is based on the folk story of the wooing of Princess Nautanki of Punjab by a local boy, Phool Singh, and is accompanied by intense melodic exchanges between two or three performers, sometimes backed by a chorus.

Watch a Bhojpuri nautanki

Melodrama, exaggeration, garish costumes and shrill music characterise the song-and-dance extravaganza jatra, which has flourished in Bengal for centuries. Jatra performances mostly centre around the life of Lord Krishna, and, as with therukoothu, all the parts are played by male actors.

Listen to a jatra rendition

Painted Scroll Narratives

Lengthy stories were often told in front of a large-scale painted textile or embroidered tapestry that expressed the colourful worlds of the stories in visual narratives. The storytellers who carried the scrolls from village to village were known as ‘picture showmen’ and each region had its prominent scroll painting traditions: Phad paintings in Rajasthan told the epic story of the folk deity Devanarayana and the Romeo-and-Juliet-style love story of Dhola and Maru; chitrakathi from Maharashtra related the story of the Mahabharata and the Ramayana through single-sheet collections of pictures supported by narration, puppets and music.

Learn how phad paintings are made

Watch a chitrakathi storytelling session

In Gujarat, there evolved the sophisticated scroll paintings of the Garodas, who painted multiple legends on a single scroll called tipanu, meaning ‘recording’ or ‘remark’; and Orissa is famous for its patachitra relating the stories of the gods in picture form. Unique to Telegana are cheriyal scrolls. They were about three feet wide and could be as long as 40 to 60 feet, depending on the length of the story. The story was presented in a sequence of panels, just like a modern comic strip, separated by straight-lined frames or a border filled in with patterns of flowers, leaves and vines. Taken from village to village, the scrolls would be displayed on a simple stage lit by lanterns whilst the narrators told their story over several nights, accompanied by musicians. (Learn more about tipanu paintings at https://tinyurl.com/CM0218-11)

Learn more about patachitra paintings

Learn more about cheriyal scrolls

Painted scroll narratives were not limited to the Hindu tradition – stories from Islam were portrayed on pirs by Bengali Muslim artists. Used as visual aides to the live narration, the scrolls were the earliest form of audio-visual entertainment.

Learn more about pir paintings at https://tinyurl.com/CM0218-14.

Storytelling Using Props and Puppets

Stories were also told with the help of props or puppets. Kaavad, which originates from a word meaning ‘panel’ or ‘half door’, is both the name given to a tradition of storytelling unique to the kaavadiya bhats, the itinerant storytellers of Rajasthan, and the portable shrine that is the focus of their narrative. Carried from house to house, the kaavad is a wooden box made like a small cupboard with up to ten hinged doors, painted all over with scenes from the epics and stories of local saints and folk tradition. The panels open and close as the story unfolds, taking listeners on a visual journey.

Watch an artist unveil the many sides of a kaavad

Puppetry is an old art that is being enthusiastically reinvented by modern storytellers. Katkatha’s show about Ram adapts the story of the Rama–Sita relationship from the Ramayana and includes dance, music, martial arts and animation as well as puppets that range from 3 inches to 25 feet high. It uses the traditional story to tackle social issues such as health awareness programmes and women’s problems. The company Ishara Puppet Theatre also seeks to innovate, integrating puppets into the storytelling style rather than using them just as props. As well as adaptations of the Rama and Sita stories, Ishara Puppet Theatre has based performances on tales 2,500 years old that tell of the wise King Vikramaditya and the spellbinding stories related to him by the wily ghost Betaal, as well as the love story of Dholu and Maru.

Watch a performance by Katkatha Puppet Arts Trust

Watch a performance by Ishara Puppet Theatre

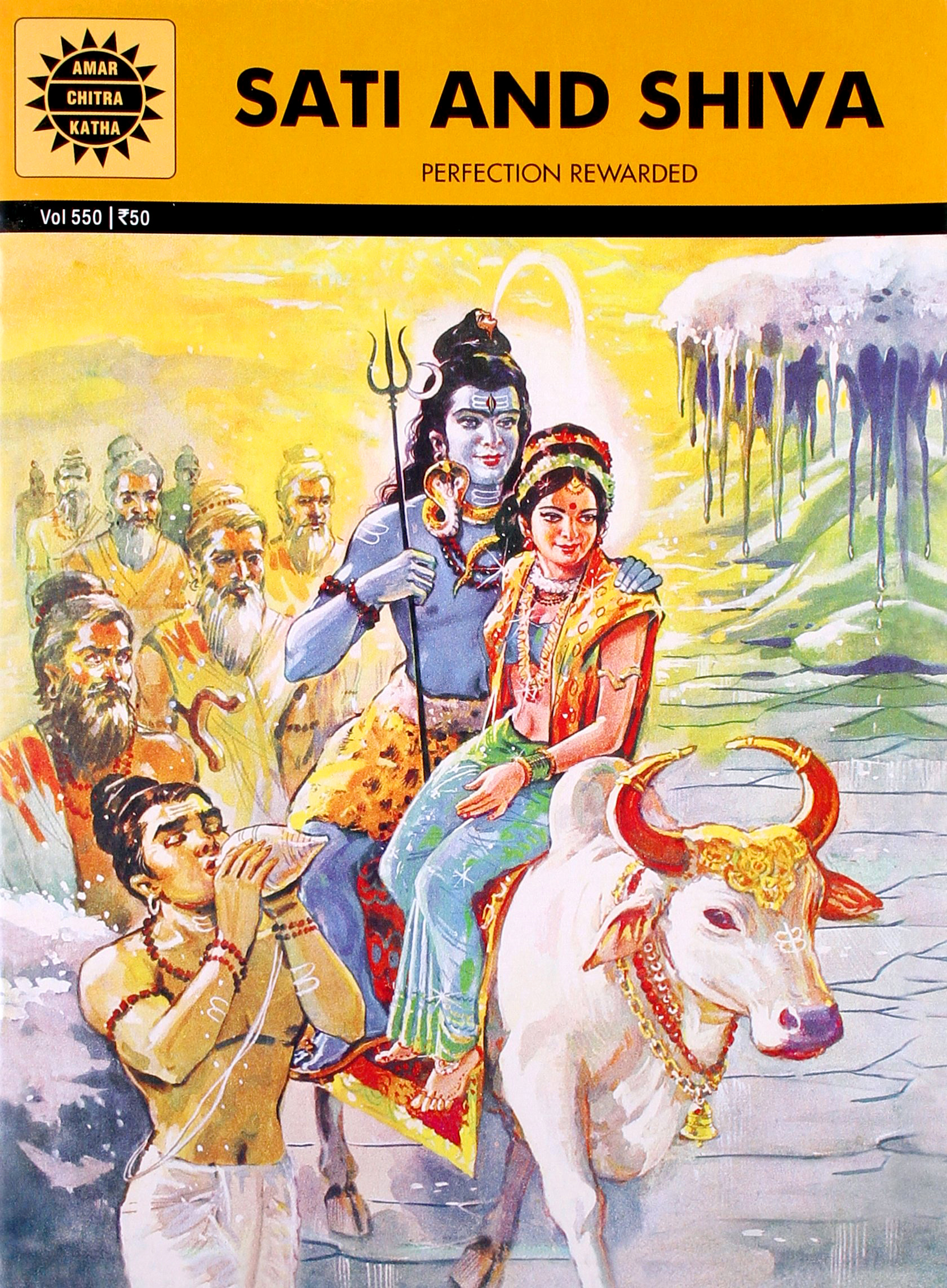

Comic Books, Graphic Novels, Cartoons and Films

Modern society offers new ways of communicating the old stories. Amar Chitra Katha (meaning ‘Immortal Picture Stories’) has published quintessentially Indian stories since 1967, and many young Indians grew up on their fables, parables and life-stories of the gods. For many the books have taken on the role of the grandmother and are the primary source of stories about India. The comic book genre has expanded in recent years, as young creatives, brought up on the Amar Chitra Katha stories, experiment with dynamic retellings of the classics in graphic novel form, turning conventional versions of the epic on their head and narrating stories of Indian mythology with a contemporary influence. India’s repertoire of stories quickly became the subject matter of television cartoons and many dramatise the lives of the gods and focus on the childhood of the deities, such as Hanuman and Ganesha, bringing children closer to India’s mythological stories. Cartoons made by Ultra Adventures found immediate success with the family market with simple animation techniques. Full-length animated films are relatively new to India’s vast film industry and recent collaborations have changed the landscape completely.