On August 15, 2014, Narendra Damodardas Modi, the Prime Minister of India, in his Independence Day address, said, “I want to appeal to all the people world over, from the ramparts of the Red Fort, ‘Come, make in India’, ‘Come, manufacture in India’. Sell in any country of the world but manufacture here. We have got skill, talent, discipline, and determination to do something. We want to give the world a favourable opportunity…Come, I am giving you an invitation.”

The Prime Minister’s words were more than just a clarion call; they marked three significant markers in India’s development as a country. One, they were testimony to India’s optimism and confidence in its own ability to create a bright future. Second, they conveyed the country’s openness to collaborate with other countries, and its decision to be a willing player in the world market – a stark departure from the sheltered approach of the post-Independence nation. Third, it seems to have stemmed from an idea that powered the Independence Movement – Swadeshi. While the earlier concept of Swadeshi was for Indians to make their own goods for personal consumption – and thereby avoid foreign goods – India is now looking to make and export to the rest of the world.

Trade and manufacturing are not new to the subcontinent. India was once one of the biggest economies on the global scene. However, policy changes – influenced by changes in the political landscape – meant a shift in gears for a few decades. During that time, a sense of unease with regard to opening up the economy and collaborating with multinational corporations persisted. However, the economic crisis of the 1990s changed the country, and made way for a shift in the country’s psyche.

A country’s economics and politics are closely linked; and it is by observing both that one can truly understand the journey a country has undertaken over several years. It is to provide this holistic sense of understanding of how just how far India has come that Culturama traces the subcontinent’s journey from the 16th century to the present day.

1500–1820

The World’s Market

India’s annual average rate of growth of GDP: 0.19%

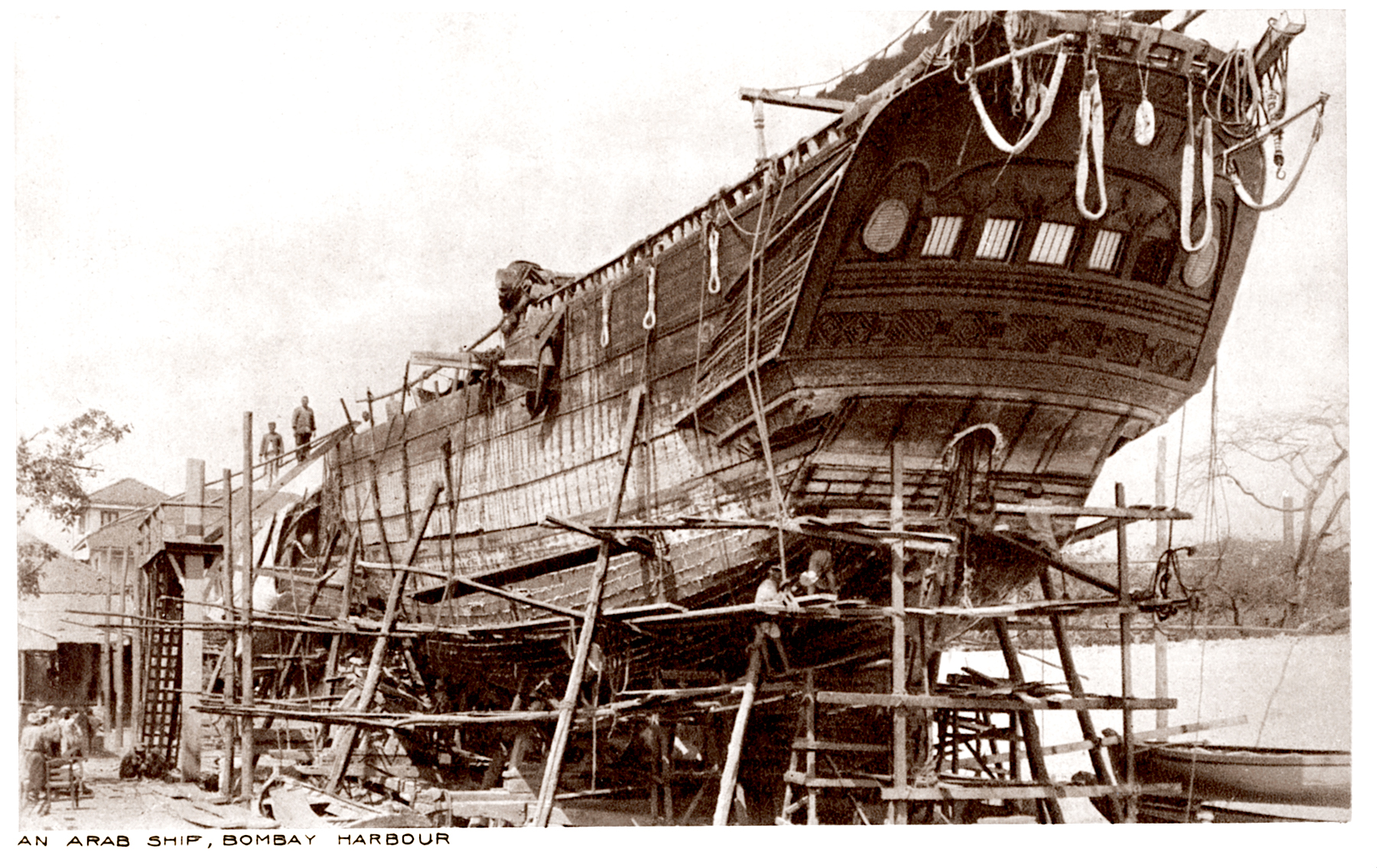

In 1700, India’s economy represented roughly a quarter of the world’s trade. A trading society since the Bronze Age civilisation of the Indus Valley, India is estimated to have had the largest economy of the ancient and medieval world until the 17th century. By the time the Mughal Empire was coming to an end, India was far more prosperous than any of the European countries whose merchants came to trade for textiles and spices. The country’s mercantile and banking institutions were sophisticated for the time, and such business ventures were formed and run by long-established trading families from India’s many castes and communities. The West Coast Parsis and Gujaratis were experienced navigators, shipbuilders and foreign traders. The Jains and Marwaris were moneylenders and bankers, whilst the southern Chettiars were a famous merchant community. To this day, members of these old trading families still dominate the business activity of the country.

European merchants had been trading with the coastal communities of India for centuries, and by the 17th century had begun to establish permanent footholds along the peninsula seaboard. The Mughal Emperor Jahangir (1605–1627) enthusiastically agreed to a commercial treaty with the British East India Company, which gave them exclusive rights to build warehouses to hold the goods they collected before shipping to Europe in return for goods and rarities from the European markets. The Company invested in textiles, particularly calico and muslin – all the rage in Europe – and by the 18th century had expanded into cotton, silk, dyes, tea and saltpetre for gunpowder.

From humble beginnings the Jagat Seth family, part of the Marwari community, had risen to become powerful businessmen and moneylenders, controlling the revenues paid by the Nawab of Bengal into the Imperial mint. Such was their status at the Mughal court that the Emperor conferred the title ‘banker of the world’ on the family’s charismatic head. They engaged with the European powers as money brokers, monopolising the exchange of bullion and lending money to foreign merchants, British, French, Armenian alike, and eventually conspired with the British to depose the Nawab of Bengal at the Battle of Plassey in 1757 in favour of a rival. This was to give the East India Company its first decisive victory in India and helped establish its principal trading colony.

1820–1870

Colonial Dominance

India’s annual average rate of growth of GDP: 0.38%

The political power of the East India Company gradually expanded throughout India from 1757 onwards. It gained the right to collect revenue in Bengal in 1765, and soon stopped importing the money it had used to pay for goods shipped back to Britain. Instead, the Company used the revenue collected from the provinces under its rule to purchase Indian raw materials, goods and spices, as well as to finance the wars it waged to gain more territory. India changed from being an exporter of processed goods for which it received payment in bullion, to being an exporter of raw materials, and an importer of the manufactured goods made possible by the onset of the Industrial Revolution in Britain and beyond. This exploitation of India’s resources devastated the economy, and delayed the country’s industrialisation.

The indigo plantations of Bengal and Bihar were an important economic aspect to emerging British power in India. This valuable dye called ‘blue gold’ was one of the most profitable commodities traded by the East India Company, which controlled production. Farmers who leased land from local zamindars (the aristocratic landowners) were compelled to grow indigo or pay a fine, and received a miserly payment for their crops. In 1859,the farmers’ resentment led to a non-violent uprising against the oppression of the planters. This was suppressed, but influenced public opinion significantly (a British official noted that ‘not a chest of indigo reached England without being stained with human blood’). Championed by Gandhi a hundred years later, non-violent resistance aimed at undermining the colonial economy was to become the route to India’s independence.

1870–1913

India’s Entrepreneurs

India’s annual average rate of growth of GDP: 0.97%

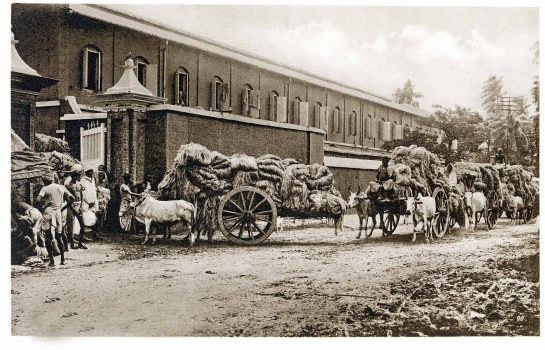

By the final quarter of the 19th century, the Indian economy had changed fundamentally. The fine cottons and silks once exported to markets in Europe, Asia and Africa were replaced by raw materials – cotton to English factories in Lancashire, opium and indigo, sugarcane and tea – and India now imported manufactured goods, often the same finished cotton fabric now returned to its origin. Yet the well-known business communities – the Jains, Chettiars and Marwaris, the Parsis and the West Coast Muslims – continued to thrive, through partnerships and trading groups that evolved into managing agency houses. These gradually bought into and replaced many British businesses, particularly in the jute and tea plantations.

Local attempts to found cotton factories in India – after all, India was providing both raw material and markets – naturally followed. Parsi businessman C. N. Davar (1814–1873) built on the family business as brokers for English commercial firms engaged in trade with India and China to participate in a number of new and successful ventures in banking, shipping and engineering, and ultimately a textile mill to spin yarn. Inspired by his enterprise, Davar’s contemporaries soon followed, and by 1862 British officials were warning that Indian competitors would inevitably undermine their Lancashire counterparts. Eighty-six textile mills had been built by 1900.

India’s greatest industrialist, J. N. Tata (1839–1904, also from the Parsi community) began his career in 1877 in the textile trade. His vision was bold from the start, importing a finer quality of cotton yarn from Egypt than available locally and, importantly, investing in sophisticated machinery from the United States whose output could compete with British imports and would make the products globally competitive. His vision was pioneering, and he identified three key areas for India: steel, electricity and scientific research. J.N. Tata laid the foundations for Tata Steel (formerly Tata Iron & Steel Company, now the world’s fifth largest steel company), the Tata Power Company Ltd. (currently India’s largest private electricity company) and the Indian Institute of Science (the pre-eminent Indian institution for research and education in science and engineering).

1913–1950

The Swadeshi Movement

India’s annual average rate of growth of GDP: 0.23%

Demands for independence were growing by the early years of the 20th century. Alongside the call for independence, there was also a call for Swadeshi, a strategy that aimed at improving economic conditions in India by following Hindu principles of self-sufficiency. By boycotting British products, reviving indigenous manufacturing and buying and using locallymade goods, Indians would ensure their resources did not leave the country’s shores.

G.D. Birla (1894–1983) was born into the Marwari community. Although his family were traditionally moneylenders, G. D. Birla began his career in the jute business in Calcutta, and saw his business soar as the outbreak of war caused supply problems throughout the British Empire. Birla Mills was established in 1919 in Gwalior, and Birla soon ventured into other enterprises, building up a huge empire scattered throughout the country that encompassed sugar and paper mills, tea and textiles, cement, chemicals, rayon, The Hindustan Times newspaper, Hindustan Motors and the aluminium producer Hindalco. Birla was a close associate and supporter of Mahatma Gandhi, and his empire encompassed almost all the sectors that independent India would need. The endeavours of pioneers such as Birla ensured that India would have the indigenous industries she needed to support meaningful independence.

1950–1973

Independence and the Five-Year Plans

India’s annual average rate of growth of GDP: 3.54%

Whilst Gandhi advocated the empowerment of village communities as the basis for the new nation, others believed that modern technology and industry would transform the economy. Congress leaders formulated a new model of mixed economic growth, which combined a centrally planned controlled economy with social justice and would balance the market and the state. Private enterprise was to subordinate its interests to the requirements of the overall plan and be content with the limited profits that were in accord with the objectives of a welfare state. Conglomerates such as those of the Tata and Birla families would continue to operate throughout the economy and were required to meet the demand for consumer goods. Meanwhile, government itself assumed direct control of heavy industry, and employment in the state sector exploded.

In the spirit of Swadeshi and to protect domestic industry, the government blocked foreign investment and set very high import tariffs. It thwarted private competition by instituting a convoluted system of elaborate licenses, regulations and accompanying red tape that earned it the nickname ‘License Raj’: up to 80 government agencies had to be satisfied before private businesses could be set up, and their production was to come under government regulation. The result was decline and economic slowdown as aspiring businessmen were put off by the regimen of approvals, and entrepreneurship was stifled. By 1973, India’s economy had declined to a 3.1% share of world income.

Not everyone capitulated, however. Dhirubhai Ambani (1932–2002) was an ambitious and energetic business tycoon who founded Reliance Industries, now one of the world’s biggest conglomerates and the first Indian company to feature in the Forbes 500 list. After a formative spell working in Yemen, Ambani began his entrepreneurial career in Mumbai in 1958, exporting spices to the Gulf States and importing polyester yarns. Soon Reliance began producing nylon textiles at a mill in Ahmedabad under the brand name ‘Vimal’, and by 1972 the textiles business was a well-established household brand across India. During the 1980s Reliance expanded into petrochemicals, and oil and gas exploration, and then diversified further into telecommunications, IT and logistics.

1973–2001

Economic Liberalization

India’s annual average rate of growth of GDP: 5.12%

Jawaharlal Nehru’s vision of a new India was created for the best of purposes – to build a proud new nation based on democracy and socialism – but it led to an over-regulation that, instead of lifting the country out of poverty, burdened it with bureaucratic hurdles and stifled its innovators. In 1991, a balance of payment crisis brought India close to default, and intervention by the International Monetary Fund began the processes of liberalising the economy and opening it up to foreign investment.

2001–2017

Doing Business in India

India’s annual average rate of growth of GDP: 7.5%

The changes made by the Indian government from 1991 onwards focused on creating export-led capabilities and building economic stability. These efforts at liberalisation have made for a consistently high economic growth rate and more opportunity for companies to do business in India. Under the new open-door policy, foreign direct investment is now possible in Indian ventures in many fields, and successful partnerships have been launched in a wide variety of sectors from construction, energy and automobiles to insurance and waste disposal!

Success in the service sector – communications, IT and the ‘back office’ projects established by so many international corporations – is the fuel for much of the country’s dizzying growth, an average of 7% annually since 1994. Bengaluru in southern India is now a global IT centre. In 2007 it boasted 150,000 IT professionals compared to 120,000 in California’s Silicon Valley, and the city’s growth has continued into this decade, with the number of new residents with technical talent outstripping that of the San Francisco area (recorded at 44% compared to 31% for California). Chennai, Hyderabad and Pune also outstripped their US counterpart as global destinations for technical talent. Many of the world’s major IT corporations – including Microsoft, Google and IBM – have a major presence in Bengaluru, whilst the number of high calibre start-ups is also on the rise.

Today, Prime Minister Narendra Modi has raised the call of ‘Make It in India’ by which he invites multinational companies from around the world to set up their businesses in the country. It shows a clear return to the roots of the Swadeshi idea – the country utilising its strengths and resources for the common good. This self-assurance also demonstrates that India has lost its fear of being dominated by other external forces, and has instead become confident that it can work hand in hand with external partners for mutual benefit. In many ways, India has come full circle, learning from the past to create a positive future.

From the implementation of GST (Goods and Services Tax) in 2017 and the inking of new trade deals with Japan including in fields such as civil aviation, trade, science and technology, and skill development, strengthening of the service and logistics sector, bolstering ties with Denmark, Korea and countries in Africa, this has been an eventful year for India that is looking to improve its economy.