She means business and her attachment to everything new and old is equally progressive. Filled with humility and passion, she finds opportunity in odd corners – be it in crafts, arts, books or sports. A thorough professional, Malavika Banerjee straddles many fields with ease. Anurima Das tries to unravel them one at a time

How do you keep the Literary Meets alive in an age where people prefer everything at the click of a button?

How do you keep the Literary Meets alive in an age where people prefer everything at the click of a button?

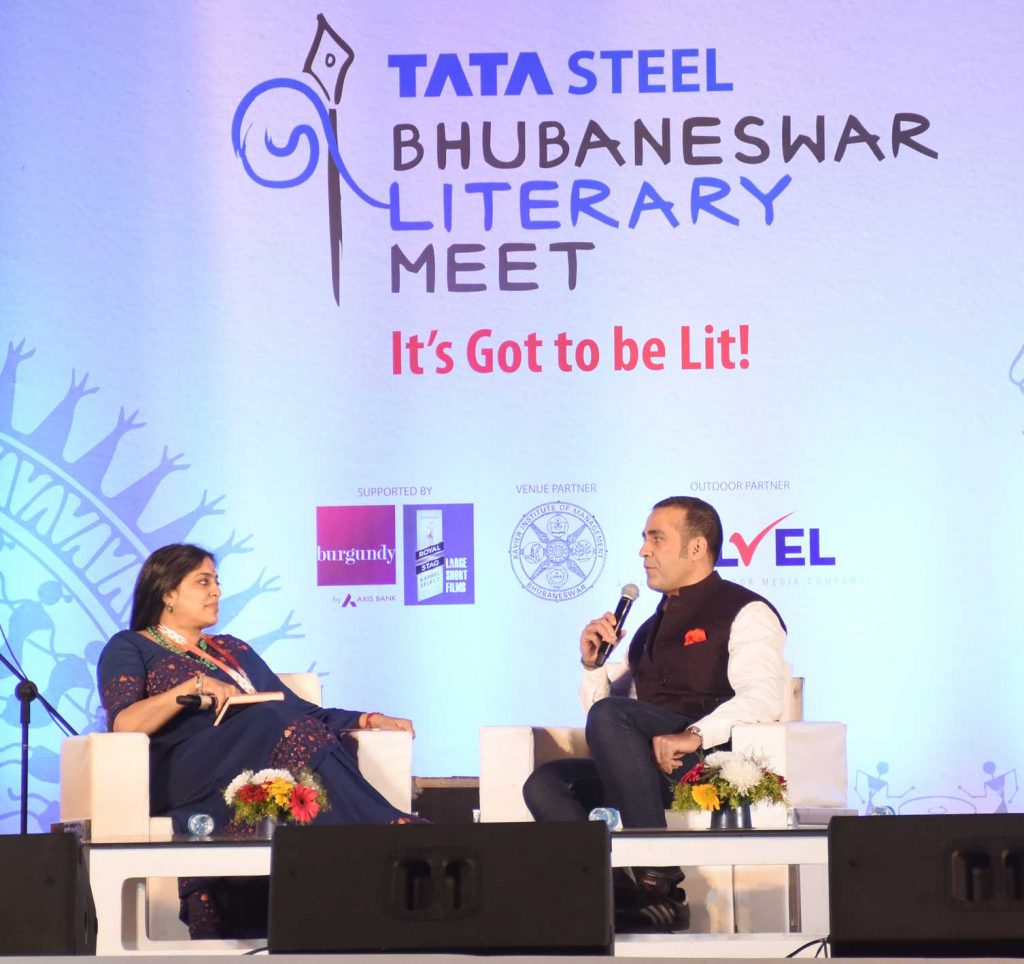

I started my journey with Literary Meets in 2012. Prior to this, I had no connection with this field except as a reader, which proved to be an advantage. I was an outsider and saw books from the reader’s perspective. So in 2012 when we started, we had no expectations from the event. Ever since, it has grown not only in size in Kolkata, but our patron Tata Steel also entrusted us with the Bhubaneswar Literary Meet four years ago and the Jharkhand Literary Meet in Ranchi two years ago. We now have many festivals to our credit.

Yes, we are increasingly leading the tech life. Paradoxically, it adds to the charm of encountering someone we have read only in print or on a gadget. However disconnected humans may have become because of these gizmos, the opportunity to personally interact with authors draws readers to the Meets.

What trends have you seen in reading habits and author mindsets over the years?

Literary festivals or meets have been happening in India for several decades in the form of mushairas, kavi sammelans and the like. The first wave of literature festivals, as we know them today, used to be overwhelmingly about writing in English. However, the response to our Bengali sessions, or even Hindi and Urdu sessions, is growing remarkably. Our initiative has shown us that audiences lead a trilingual life, at least in Kolkata. In Bhubaneswar, we do Oriya sessions, while in Ranchi it is largely in Hindi. I see that vernacular literature is also of great interest even to young readers. They read beyond one language, or at least want to engage with the vernacular writers, which is very heartening.

Please give us a sneak peek into your journey as a serial entrepreneur?

Please give us a sneak peek into your journey as a serial entrepreneur?

I’ve had wonderful colleagues along the journey. We started with a sports marketing company (Gameplan) 20 years ago, and from 1998 to 2011, we were just that. Then I personally decided that saris in particular, and handloom in general, were of interest to me and what I had learnt from marketing would be of use in setting up a retail outlet, Byloom, with partner designers Bappaditya and Rumi Biswas. As for the Literary Meets, I would dispense with false humility and say it was a lonely journey for the first year or so because it was a huge leap from sports marketing to literature. I let life throw opportunities at me and do my best to embrace them. Importantly, I’m not particularly afraid of failing. I think it’s absolutely fine to be mediocre and fumble for the first couple of years, to learn to accept failure as nothing personal and as something to learn from. So in all these fields, that is what has helped and I’ve had a lot of support.

Tell us a little about making Gameplan what it is today.

When we started Gameplan in 1998, sports marketing and promotion was very new in India. Since I came from a journalistic background, we started with just content, sending articles by experts, former and present cricketers to newspapers across India. Within a couple of years, the huge Internet boom further boosted the need for content, which we were able to cater to — it became our USP that set us ahead of the rest. We diversified into other areas of sports marketing such as player management and as retainers for various companies for their sport sponsorship activation — which comes under sports marketing. It has been a 20-year journey in which we’ve been able to ride the waves that have hit the industry successfully, including managing somebody like MS Dhoni, and the IPL where we are closely associated with the Kolkata Knight Riders. We have been able to use our skills to match the requirements of the industry at every point. Gameplan is the backbone of everything else we do, including the Literary Meets.

From a journalist to a woman entrepreneur, what was your journey like?

From a journalist to a woman entrepreneur, what was your journey like?

I was still working with newspapers, still working on articles; it was just a different way of working. But as the company grew, I realised I was no more a journalist or a salaried person, I was responsible for giving out salaries. My husband Jeet (Banerjee) and I set up Gameplan, so now it was our responsibility to work things out. It certainly required a shift in mindset. I was the mother of a young child and another child came along. So, all through those initial years, it was a journey in itself.

Technology helped me manage my work from home: my generation of mothers could have flexible hours while managing our children. It also made me sensitive to the needs of my colleagues in similar situations. So entrepreneurship, by God’s grace, has not been a very rough ride. It had its own challenges, but they were not earth-shattering; and the idea is to be always confident and ready. Be confident so that you’re ready to take up a new project. And, be prepared so that if it fails, you have something to fall back on.

Being a woman entrepreneur never made any difference, even in sports. When I started, there were only one or two women journalists in sports, but that changed within a couple of years. Between 1999 and 2003, the two cricket World Cups, there was a huge change. I realised that I was my own boss; I work on my own terms. But I say this with some caution — it doesn’t mean that you can work less. You have more flexibility but you have to work harder.

Who inspires you?

I’m inspired by several people such as authors Toni Morrison and Elif Shafak. I find many writers inspiring. I’ve great admiration for Vikram Seth, a genius whom I know personally. I’ve great admiration for Amitav Ghosh, another author I know personally and find to be very disciplined and one of the well-honed writers of our times. I’m also inspired by a lot of people in arts and culture. I’m inspired by Pupul Jayakar, who did a lot of work in the 1970s for Indian textiles and handloom.

Having tried your hands at so many things, what next?

Having tried your hands at so many things, what next?

I hope in the next eight to nine years I’ll be able to walk away from all this and work on something very important for India — ‘daylight saving’. I feel the North East should have a separate time zone, which will make them feel more a part of India.