Storytelling is an intrinsic part of Indian culture – with stories told not merely to entertain but to educate as well. One of the famous examples is that of the Panchatantra fables, set in the jungle and featuring animals as the main characters, which was ideated and narrated by a scholar named Vishnu Sharma to impart the lessons of kingship and ruling to three unruly princes.

Similarly, stories from the epics such as Mahabharata and Ramayana, parables from the Jataka Tales and folk tales from the different regions have been kept alive thanks to the art of storytelling. A common element of these stories was a value that was enclosed within a cocoon of characters, a plot and a spell-binding climax. It might involve a ghost who threatened to kill a king, a devout man who was being tested by God, or even a crafty stork that tried to eat up all the fish in a lake. However, no matter how different, the stories usually ended with the good being rewarded and the evil being punished. Thus, hidden in the stories were lessons to lay the foundation for a life well lived. Here, we share a selection of popular stories that have captivated the imaginations of children and adults alike through generations

The Lord’s Bride

The Tamil month of Margazhi, which begins from approximately December 15 and culminates in Pongal (harvest festival) in mid-January, is considered to be one of the holiest months in the Hindu calendar. Devotional hymns written by the alwars (poet saints) are rendered throughout the month. The most popular of the hymns is the Tiruppavai consisting of 30 verses in praise of Lord Vishnu attributed to Andal, one of the 12 alwars.

The story of Andal is set around the 8th century in a village called Srivilliputtur (Sri-villi-putt-ur) in central Tamil Nadu. At the Vishnu temple, there was a garden that was tended faithfully by a devotee called Periaazhvaar (Peria-azh-vaar). The flowers for making garlands for the Lord came from here. One day, while deepening the pit of the tulsi (holy basil) plant, he miraculously found a baby girl. Considering it to be God’s gift, and being childless he and his wife decided to rear the child and named her Kothai (meaning ‘from Mother Earth’) but later called her Andal.

Andal was very devoted to the Lord and particularly enjoyed making the garlands that her father took every day to the temple. One day, Periaazhvaar found some strands of hair in the garland. Not too sure how they appeared, as he always took great care when making them, he decided to keep a careful watch. What he saw shocked him – Andal wore the garland meant for the deity and admired herself in the mirror before she placed them in the basket to offer the Lord. This was sacrilege according to Periaazhvaar. Hindus will not even smell flowers that are to be offered to God as this will make them impure!

He confronted Andal and, to his surprise, she did not show any remorse. She confounded him by replying very calmly, “Why can’t I wear them? After all, I am going to be his wife.” Periaazhvaar was deeply troubled by this sacrilegious statement. However, that night, the Lord appeared in his dreams and said that he did not want fresh flowers but only those worn by Andal. Such was the purity and depth of her devotion. Periaazhvaar’s doubts were put to rest and the whole town soon came to recognise Andal’s devotion.

Andal soon grew into a young woman and her father wanted to find a suitable match. But she persisted in her resolve that she would marry only the Lord. Her father was in despair. Who could marry God? One day, Andal insisted on being taken to the famous Sri Ranganatha Temple (near Trichy). When her father did so, it is said she was so ecstatic at the sight of the Lord that she disappeared into the sanctum sanctorum and became one with the deity. Thus was she united with the Lord. Almost every temple of Vishnu has an altar dedicated to Andal and the gardens of Srivilliputtur exist to this day.

If you are in Tamil Nadu, look out for the Margazhi celebrations from mid-December onwards. At the Vishnu temples, in the early morning before the sun rises, groups of devotees will go around singing hymns – many of which have been written by Andal.

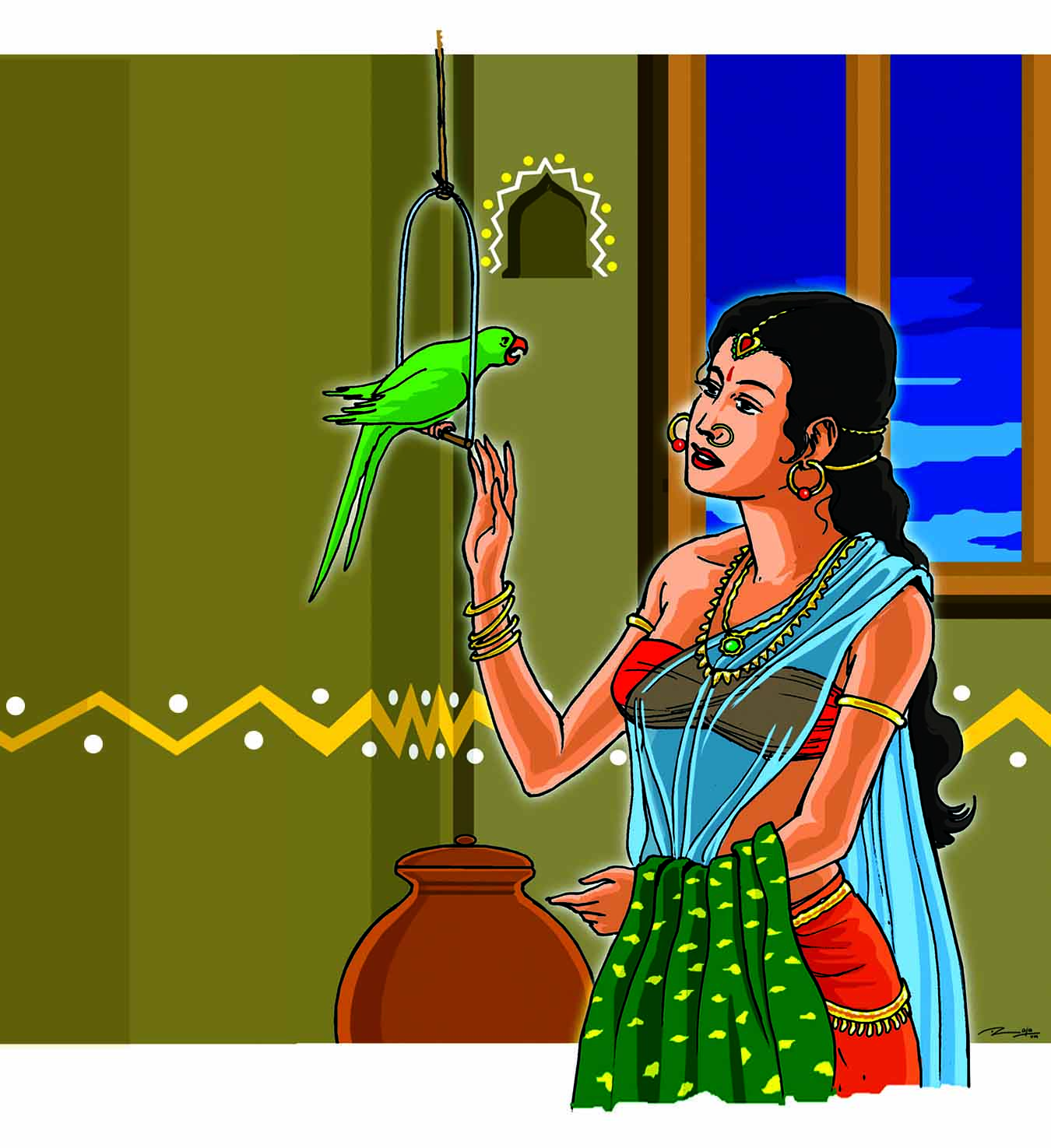

Seventy Tales of a Parrot

A collection of satiric, mischievous wives’ tales with morals, Shuka Saptati (‘The Seventy Tales of the Parrot’) dates back to well before the 14th century. The structure is of stories within a story. In a city lived a rich merchant whose one sorrow was his wayward son, Madan. The young man was given to many vices. A close friend of the distraught merchant took pity on him and gifted him a parrot, saying that this bird could be his family’s salvation.

The merchant gave the parrot to his son. Madan was happy to have a new distraction in his dissipated life. One day, to his delight, the bird began to talk to him. Perhaps it was this novelty that led Madan to listen to the parrot as it began to try drilling sense into him. The parrot (shuka) warned Madan that his self-indulgent ways would lead to his fall, and told him a story to illustrate this. Madan was moved to see reason. Determined to reform his life and make his fortune, he took leave of his family and went to another country. He left behind him a very young wife, Prabhavati, who soon became unbearably lonely. To make it worse, she had some rather dubious friends who playfully suggested that she take a lover. Prabhavati was eventually tempted.

As she was leaving the house on the first night she was to meet her lover, the parrot asked her where she was off to. “I am going to see what it is like to take another man for a lover,” said Prabhavati. The clever parrot, instead of stopping or berating her, merely said, “That is fine and merits doing. However, if you are caught, you will lose your reputation. Are you sure you have the wit to get yourself out of any problems that may arise, like the merchant’s wife whose own husband was brought to her as a lover?”

Prabhavati was intrigued and begged for the full story. So, the parrot began the first tale of Shuka Saptati. It talked about the love a merchant had for the wife of another. But this woman refused to be unfaithful to her husband. So, the lovelorn man employed a professional go-between who set about befriending the virtuous woman and cunningly persuaded her to succumb. However, on the day of the assignation, the lover was unavoidably detained elsewhere. As the woman was all aflame, she demanded that any man be brought.

The go-between went out and whom should she bring back but the woman’s own husband! The wife was shocked but recovered quickly. She attacked her husband, yelling, “You rogue! You claimed you had eyes for no other woman. See how you have failed the test I set you!” It took the husband a long time to convince his wife to forgive him. There, the parrot ended its first story.

A little intimidated, Prabhavati stayed home that night. The next night though, she made ready to leave again. Again, the parrot delayed her with similar tactics and told her another story. Sixty-nine nights passed in this way with the parrot telling her stories with hidden morals.

On the seventieth day, Madan returned home. The parrot led Prabhavati to confess her near infidelity to her husband but, when Madan seemed angered, quickly told him another story that preached forgiveness of a fault that arose from circumstances, and persuaded Madan to pardon a wife who had strayed more in thought than in deed. Thus ended the seventieth tale.

The Umbrella Thief

This is the story of a demon called Naraka who snatched away the umbrella of Varuna, the God of Water.

Naraka was the son of Mother Earth and had perpetrated many evil acts in his demonic way. Indra, the King of Rains and the Lord of the devas (gods), was vexed with him and went to Lord Krishna (an incarnation of Lord Vishnu) to seek help to destroy the demon. Indra related to Lord Krishna the nefarious activities of Naraka that were an affront to his sovereignty over the devas.

Naraka had snatched away the umbrella of Varuna. He had also stolen the earrings of Indra’s mother, Aditi, and had evicted Indra himself from his abode, Mount Mandara, and taken the jewels that crowned it. Indra wanted Lord Krishna to put an end to the demon’s unrighteous acts. Hence, Krishna, who had taken his present avatar (incarnation), to put an end to unrighteousness and uphold the righteous, proceeded to face the demon.

Earlier, Lord Krishna had given a boon to Mother Earth that he would not kill her son without her permission. To uphold his promise, yet put an end to Naraka, he took his wife, Satyabhama, to aid him as she was an incarnation of Mother Earth. The fight with the demon and his associates followed and many were the weapons that were used against Lord Krishna, but nothing could harm him. Finally, Lord Krishna used his sudarshanachakra (discus) and lopped off Naraka’s head. (The killing of Naraka is one of the many stories associated with Deepavali/Diwali, the festival of lights.)

Mother Earth delivered to Lord Krishna the pair of earrings belonging to Aditi, Varuna’s umbrella and Indra’s crest jewels. Bending low with humility, Mother Earth praised Lord Krishna’s powers and sought his blessings. Indra felt duty bound to retrieve the umbrella that belonged to Varuna.

Indra is also famed for bringing torrential rains – like he did to the cowherds of the legendary Vraja. Lord Krishna had to lift an entire mountain with his little finger and hold it aloft for seven days to protect the cows, cowherds and villagers who had taken shelter under it from the rains.

The Bond of Brotherhood

While Deepavali is a one-day festival in South India, the same (called Diwali) is an elaborate five-day affair in the North, with each day having its own religious significance and associated legends. Every year, Bhai Dooj, a celebration of the brother–sister bond, is observed on the final day of the five-day festival all over North India. (Bhai means brother.)

On this day, brothers visit married sisters and are welcomed with a traditional tilak, or a mark of vermilion on the forehead, which is said to protect them from evil. In return, they renew their pledge to protect their sisters in times of need. Perhaps this festival evolved in response to a need for married women to keep alive the links with their parental home. Perhaps it was society’s way of reassuring the vulnerable dependent married woman of a fallback support system she could rely on, in case of distress.

Whatever the reasoning behind this annual ritual, as in all such cases, there is an enchanting story that seeks to explain how it all began. The tale goes that in the early days of creation, the first human pair, Yama and his twin sister, Yami, walked the earth, basking in the warmth of the ever-shining sun (there was no night then), deeply bound by their love for each other. Mad with love for her brother, Yami even importuned him to take her as his wife. But Yama, ever conscious of right and wrong, firmly refused to be drawn into this sort of a relationship. In course of time, the scriptures say,

Yama embarked on a quest to find “the home of the fathers from which one is never taken away,” that is, a quest to understand the significance of death in human life. He found his way to the land of no return and assumed responsibility as its overlord.

Back on earth, Yami was distraught with grief at the loss of her brother. Her loud lament attracted the sympathy of the gods. When they tried to console her, Yami wept, “But how can I forget? He died only today!”

The gods realised that it was the immediacy of her grief that made it so poignant and painful for her. They introduced ‘night’ into the world, with its soothing darkness to brush away cares, relieve stress, and pacify the agitated mind. By introducing a stretch of time between one day and another, the Gods helped Yami to overcome the aching memory of her brother’s death.

However, once every year, Yama visited Yami on earth – and in their annual renewal of fraternal love lies the seeds of Bhai Dooj.

Bhai Dooj is just one of a number of festivals in India that celebrates family relationships. The family has always been revered as an important building block of society and the relationship between members of a well-networked family are held to be sacrosanct and inviolate even today.

The Goddess’s Earring

Thiru Kadvooror Tirukadayur (ti-ru-ka-da-yu-r) is located in Mayavaram, 250 km south of Chennai. Here, Lord Shiva presides as Amritaghateswar (am-rit-a-ghat-eswar) with Goddess Abirami as his consort. It is one of the important pilgrimage centres of Lord Shiva. Legends are associated with both Lord Shiva and Goddess Abirami.

An unusual story is that of a man named Abirami Battar. About 250 years ago, Abirami Battar was born into a family of temple priests who, for generations, had worshipped the Goddess in Mayavaram. Abirami Battar was different from the others in the depth of his devotion. He would spend hours in front of the deity, immersed in her. He would sing in her praise and often go into a trance. Nothing seemed important to him other than the Goddess. News of his devotion spread and people flocked to see this great devotee. However, there were some people who did not like this popularity. They believed that Abirami Battar was only feigning devotion.

It was the reign of the Maratha King Serfoji of Thanjavur. One day, he came to visit Tirukadayur to offer tributes to the presiding deities. He had heard of Abirami Battar’s devotion and went to meet him. As usual, Abirami Battar was unaware of what was going on around him. Starting a playful conversation with the priest, the king asked whether the next day was a new moon day or a full moon. Lost in thought, the priest answered that it was a full moon.

The king was taken aback since it was the waning phase of the moon and it would be a new moon. Convinced that the priest was only a dupe, or perhaps piqued by his seeming inattention, he ordered that the priest be beheaded if there was no full moon the next night. He then returned to his palace. Abirami Battar realised his folly and wept before the goddess, pleading for her mercy. He began a passionate appeal that took the form of singing a series of verses in her praise. The verses were unique because the last syllable of a verse was the first syllable of the next verse. It is still available to us as Abirami Anthadhi (meaning ‘Abirami: the Goddess without Beginning or End’; anth is end, adhi is beginning).

As he sang, the king and the people gathered to see how Abirami Battar would save himself. Was he a devotee worthy enough for the goddess to rescue or would he face the executioner? Seventy-eight verses had gone by and he was getting closer to death when the miracle happened.

Moved by her devotee’s plight, the goddess is said to have taken off her earring and thrown it into the sky. The dark sky lit up as though the moon were in full splendour. Thus, Abirami Battar was saved.

One more colourful version of the legend has it that Abirami Battar lit a fire in a pit and suspended himself from a hundred ropes before he began singing. As he completed each verse, a rope snapped, bringing him closer to death. Seventy-eight ropes snapped before the miracle happened. The goddess blessed him and he continued to finish the hymn, 100 verses in all.

The king was so ashamed for having doubted the integrity of such an ardent devotee that he begged forgiveness. He presented copper plates with inscriptions of this feat to the priest. It is believed to be in the possession of the descendants of Abirami Battar’s family.

Just in case you are wondering, Abirami Anthadhi is still sung by many a household in Tamil Nadu today.